Stevens v Brodribb Sawmilling Co Pty Ltd (1986) is a case of workplace negligence. The case revolves around the distinction between an employee and an…

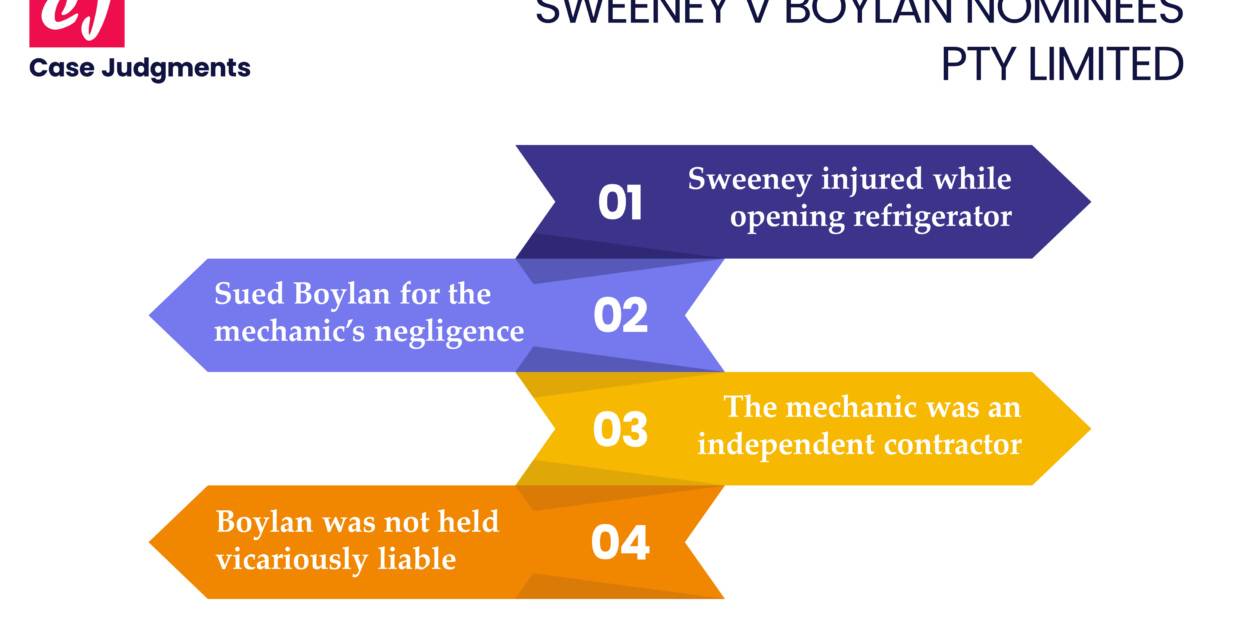

Sweeney v Boylan Nominees Pty Ltd [2006] is a famous labour law case from Australia. Given below are the case facts. Facts of the case…

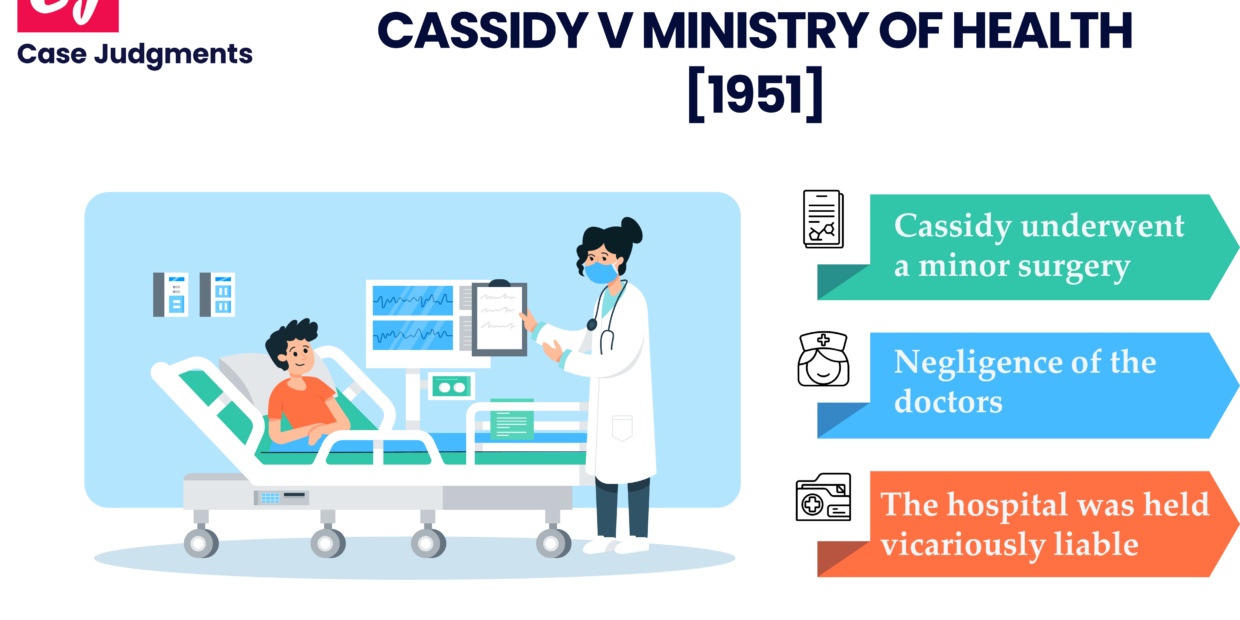

Cassidy v Ministry of Health [1951] is an important tort and labour law casethat deals with the concept of Res Ipsa Loquitur (Latin for “the…

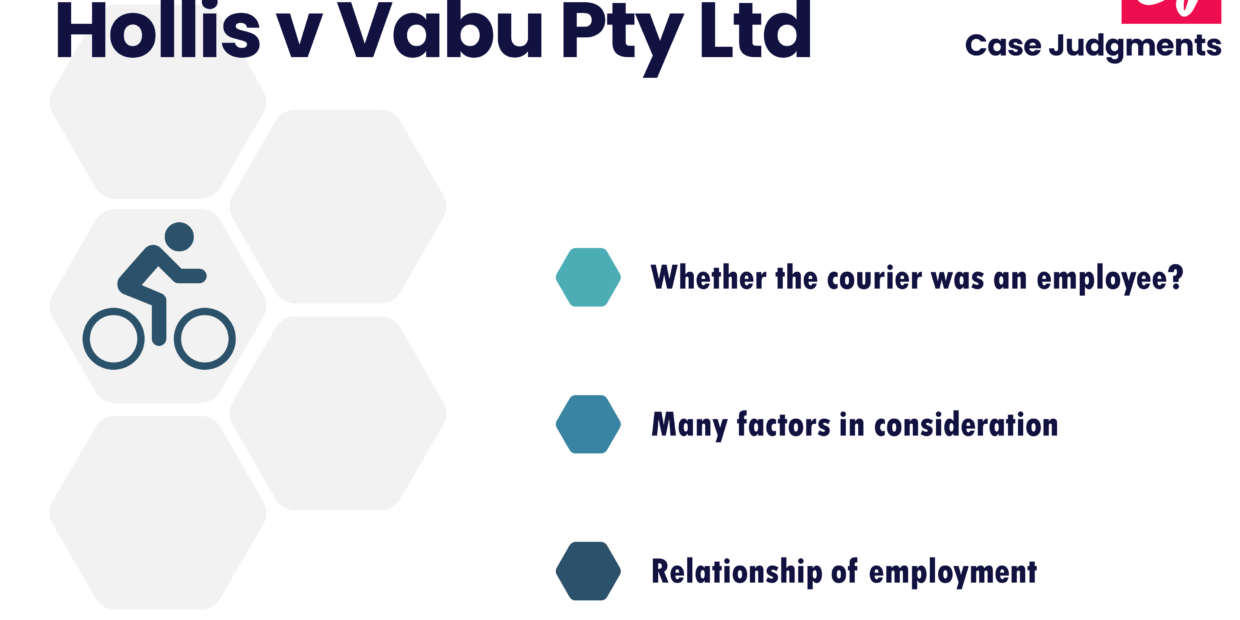

Case name & citation: Hollis v Vabu Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 44; (2001) 181 ALR 263; (2001) 207 CLR 21 The concerned court: High Court…

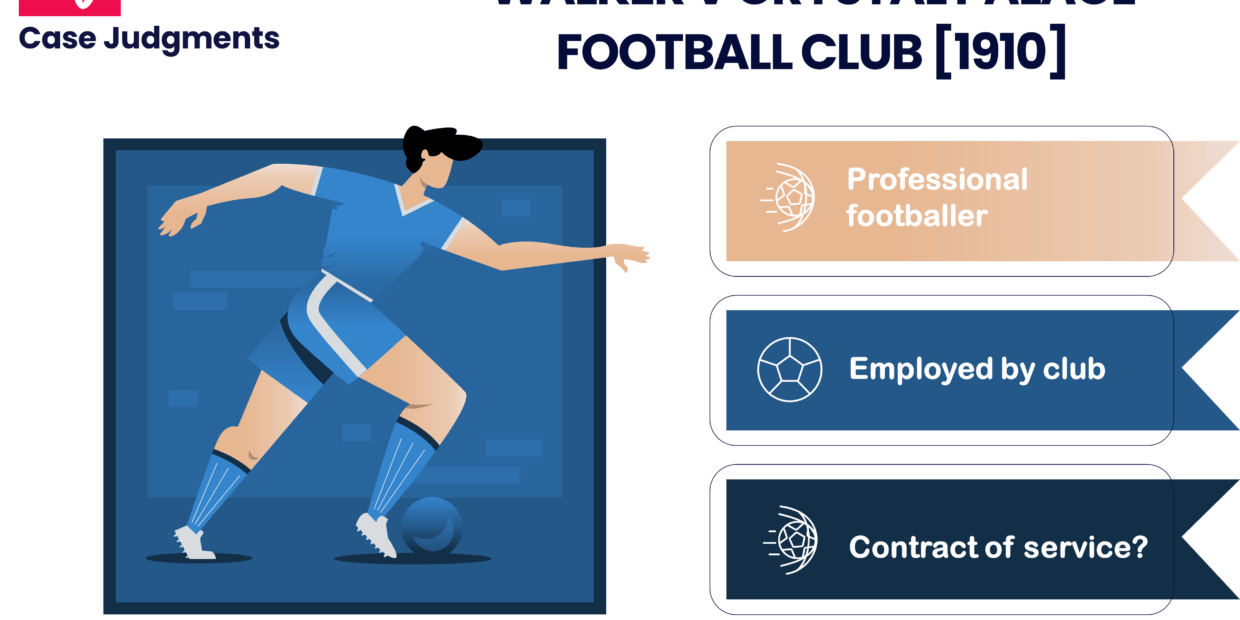

Case name & citation: Walker v Crystal Palace Football Club Ltd. [1910] 1 KB 87 Court and jurisdiction: The Court of Appeal, England and Wales…

Case name & citation: Yewens v Noakes (1880) 6 QBD 530 Court and jurisdiction: The Court of Appeal, England and Wales The learned judge: Bramwell…