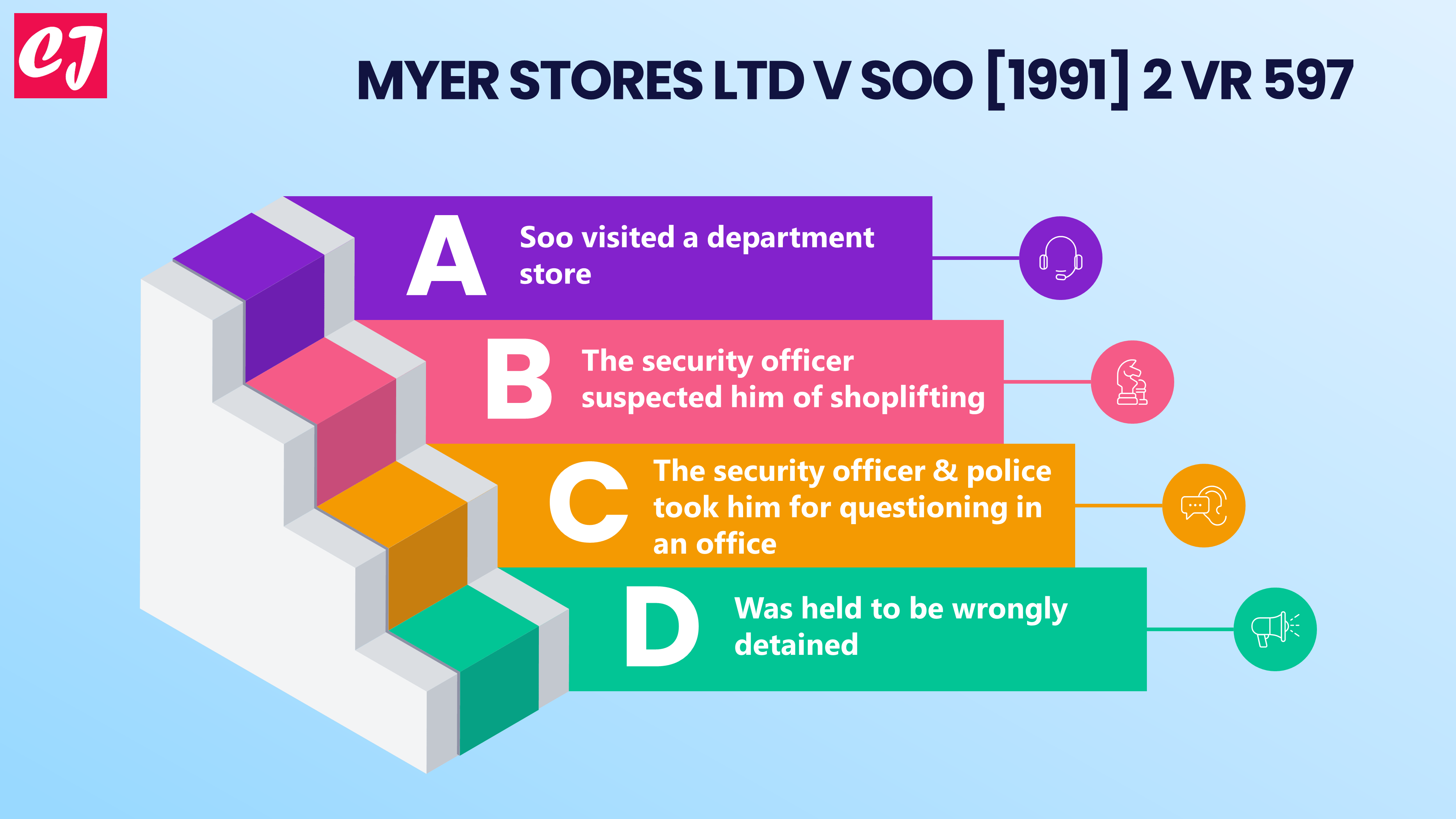

Myer Stores Ltd v Soo [1991] is an Australian tort law case concerning the detainment of a customer at a departmental store. The question arose…

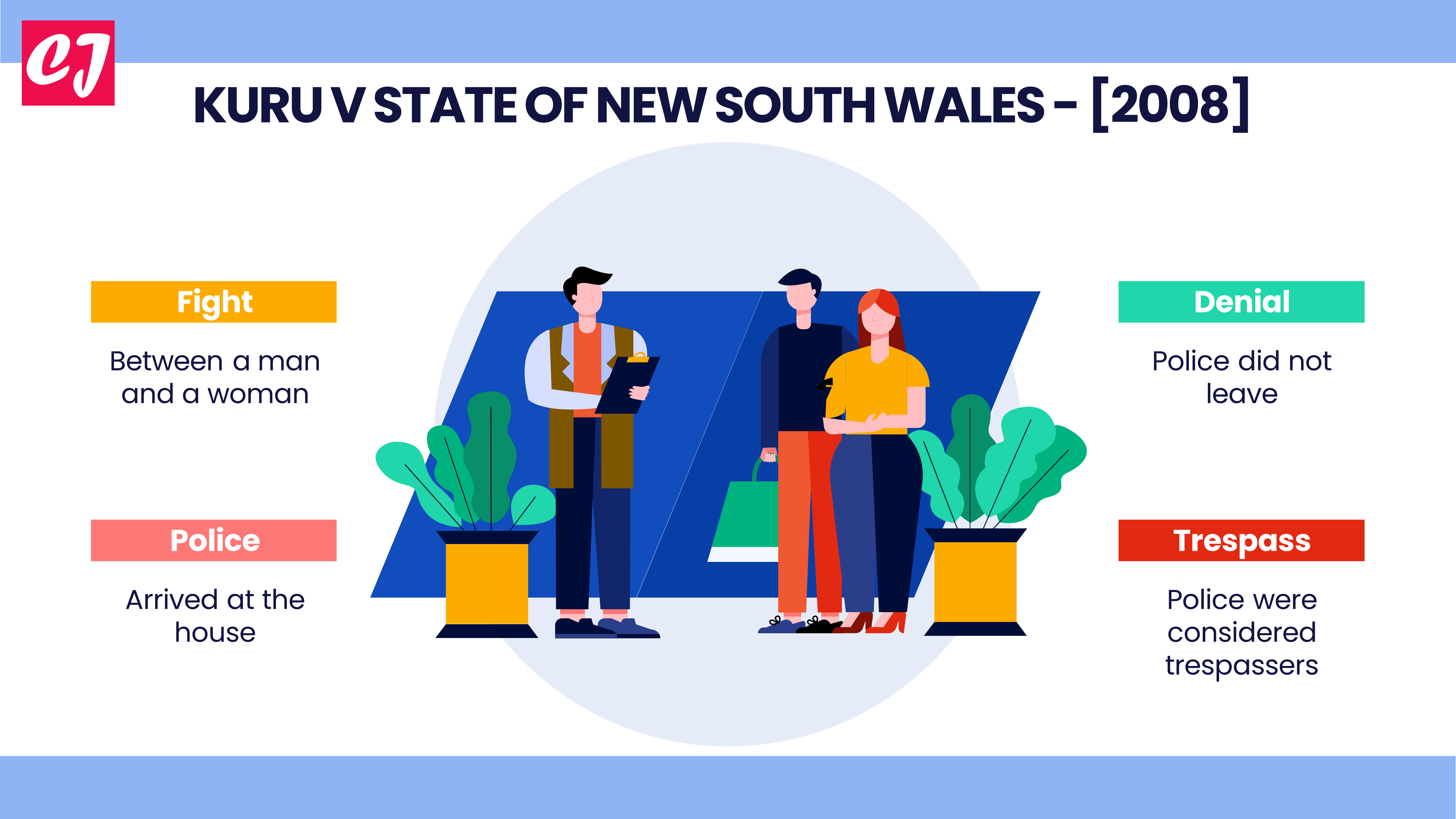

Kuru v NSW [2008] is a tort law case on issues of trespass and false imprisonment. Case name & citation: Kuru v State of New…

Mcfadzean v CFMEU is a case on the tort of false imprisonment. Some environmentalists took part in anti-logging protests and were allegedly imprisoned by logging…