L’Estrange v Graucob [1934] is a famous contract law case that is known for laying down the rule that the contents of a signed contract…

Curtis v Chemical Cleaning and Dyeing Co [1951] is a famous contract law case that dealt with the issue of misrepresenting a term. It determined…

Darlington Futures Ltd v Delco Australia Pty Ltd (1986) is an Australian case in which the High Court of Australia confirmed that professional persons might…

Case name & citation: Causer v Browne [1952] VLR 1 Decided on: 12 October 1951 The learned judge: Herring C.J. Area of law: Exclusion of…

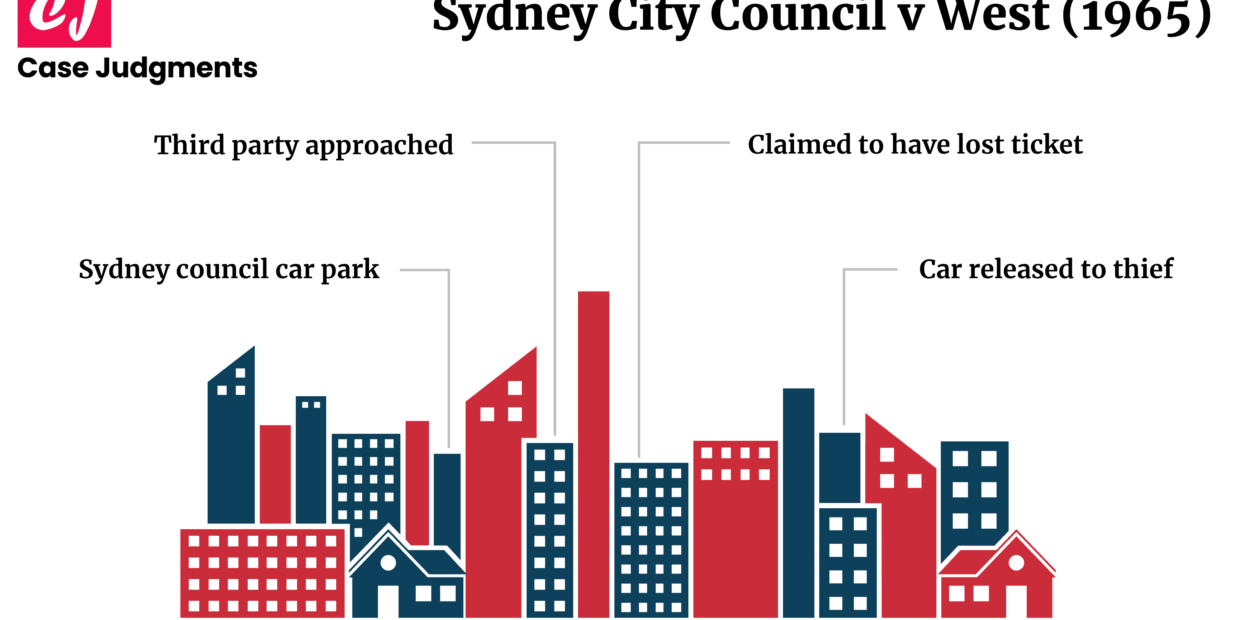

Case name & citation: Sydney City Council v West (1965) 114 CLR 481 The concerned Court: High Court of Australia Decided on: 16 December 1965…