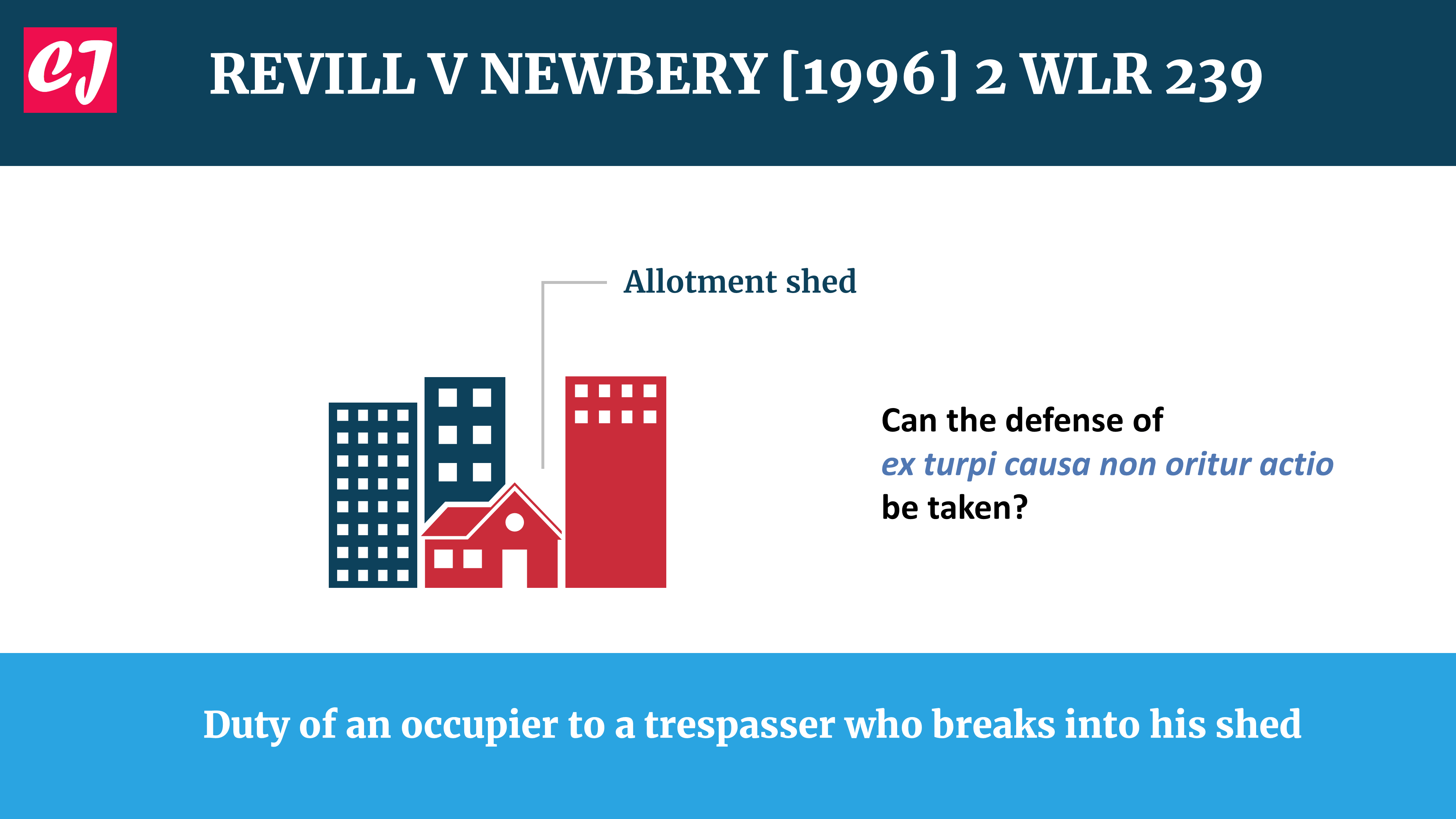

Case name & citation: Revill v Newbery [1996] QB 567; [1996] 1 All ER 291; [1996] 2 WLR 239 What does the case deal with?…

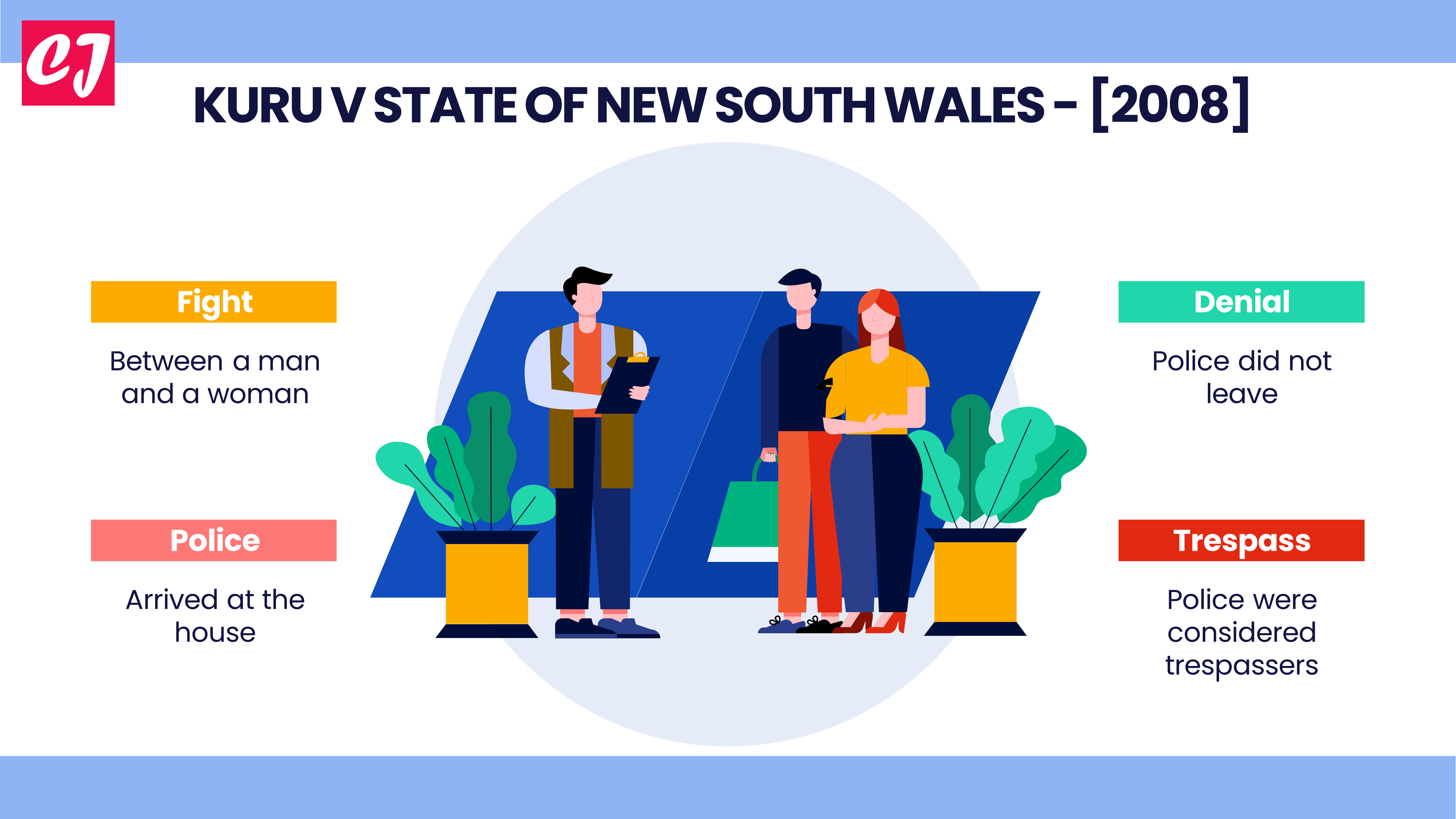

Kuru v NSW [2008] is a tort law case on issues of trespass and false imprisonment. Case name & citation: Kuru v State of New…

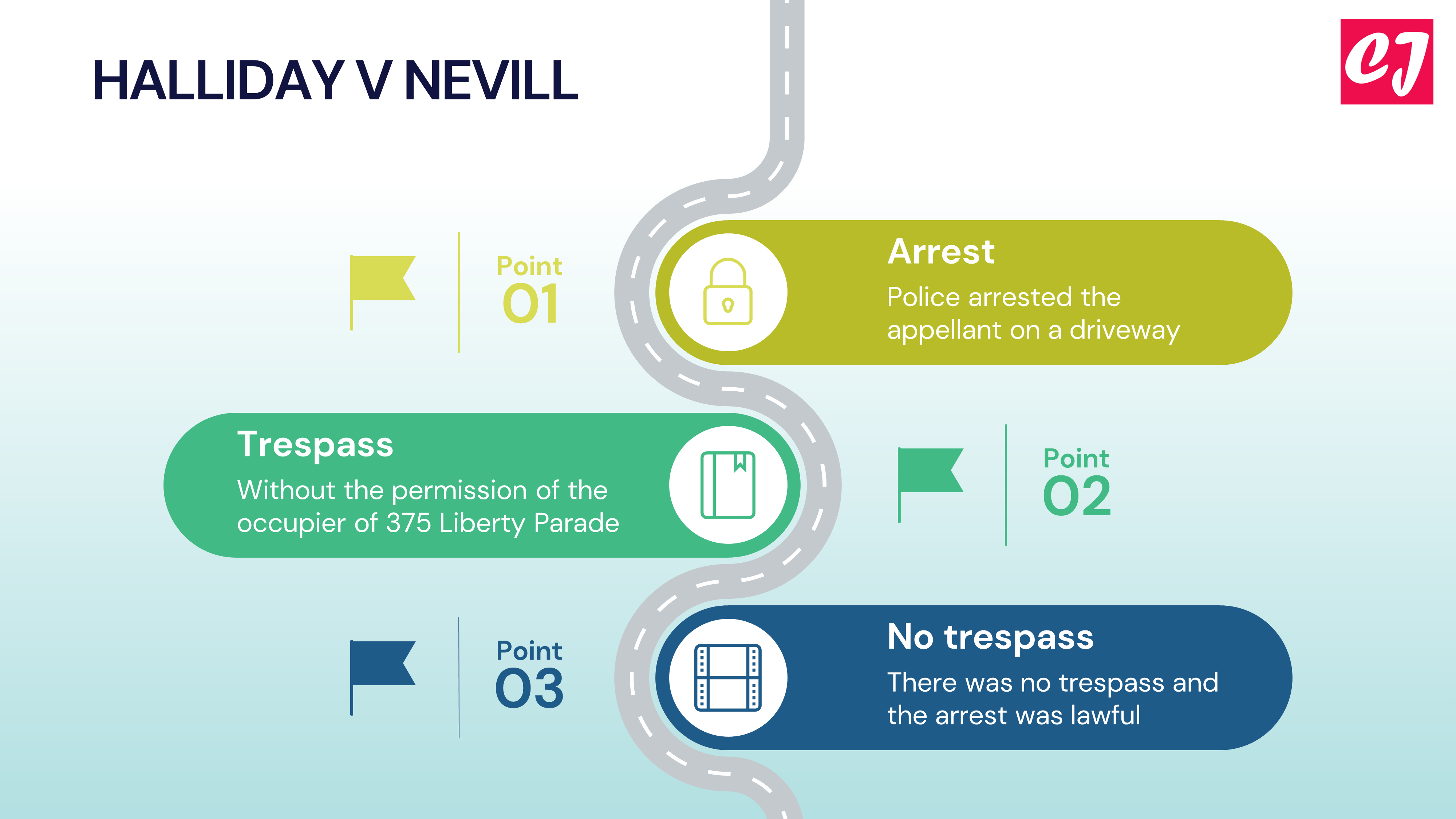

Case name & citation: Halliday v Nevill [1984] HCA 80; (1984) 155 CLR 1 Facts of Halliday v Nevill This is an appeal case originating…

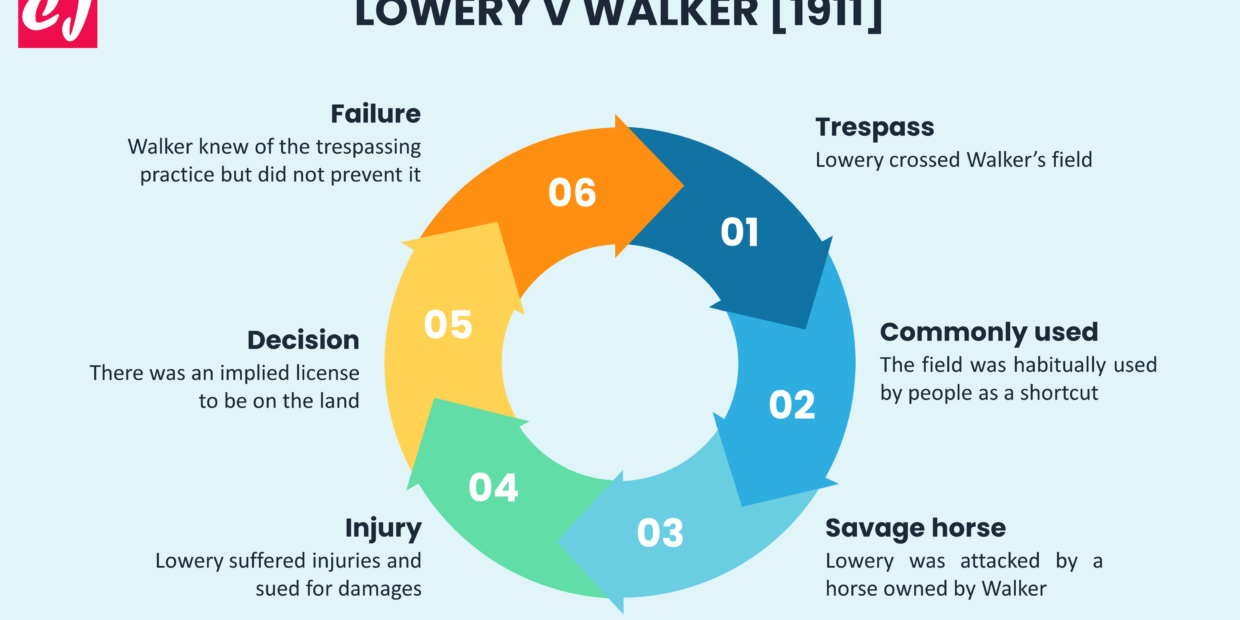

Lowery v Walker [1911] is a UK tort law case concerning the liability of an occupier to people habitually crossing his land and the occupier’s…

Case name & citation: Hackshaw v Shaw [1984] HCA 84; (1984) 155 CLR 614 What is the case about? Hackshaw v Shaw [1984] is a…

Cowell v Rosehill Racecourse Co Ltd [1937] is a tort law case from Australia differentiating between contractual rights and property rights. Case name & citation:…