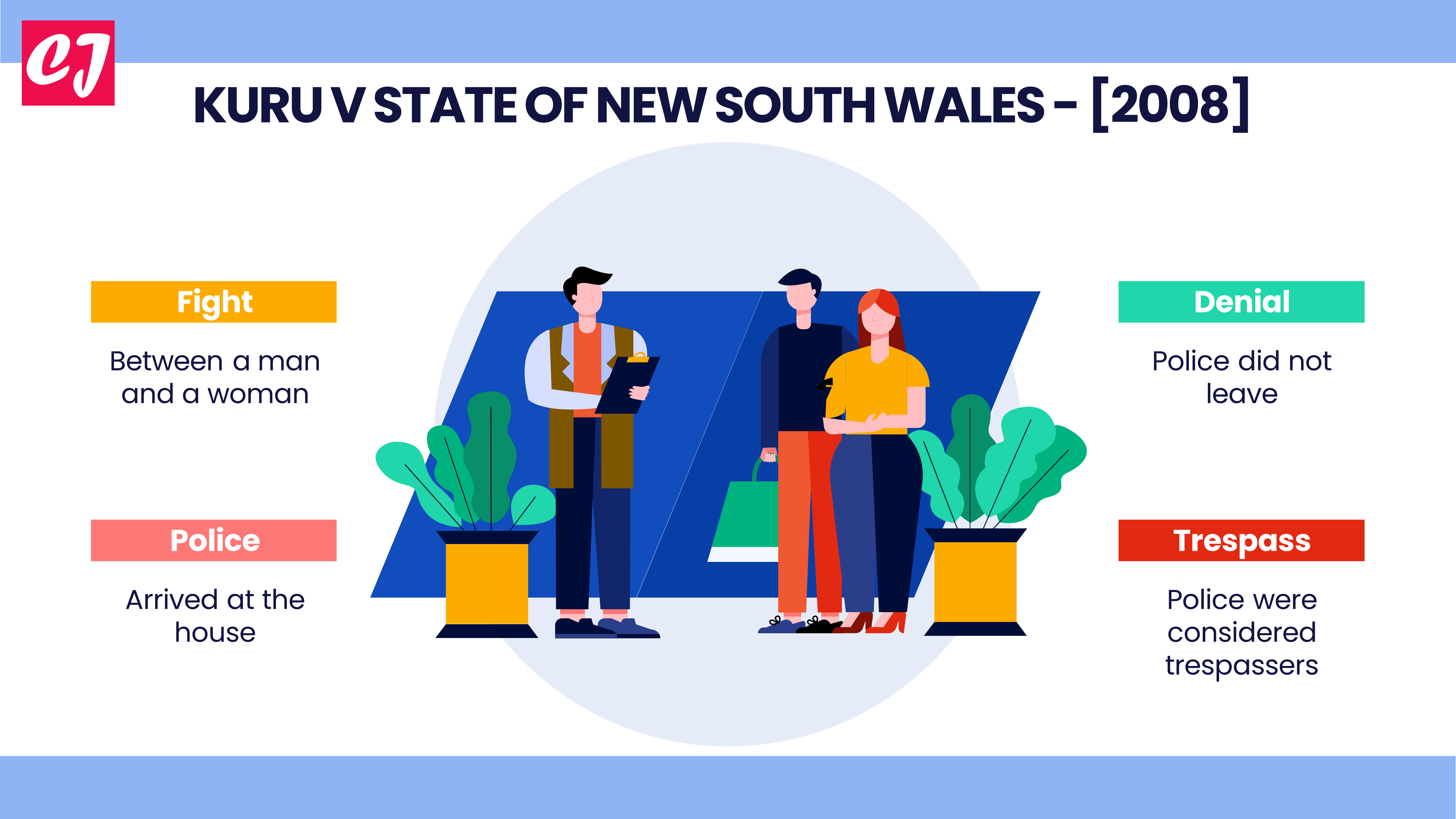

Kuru v NSW [2008] is a tort law case on issues of trespass and false imprisonment. Case name & citation: Kuru v State of New…

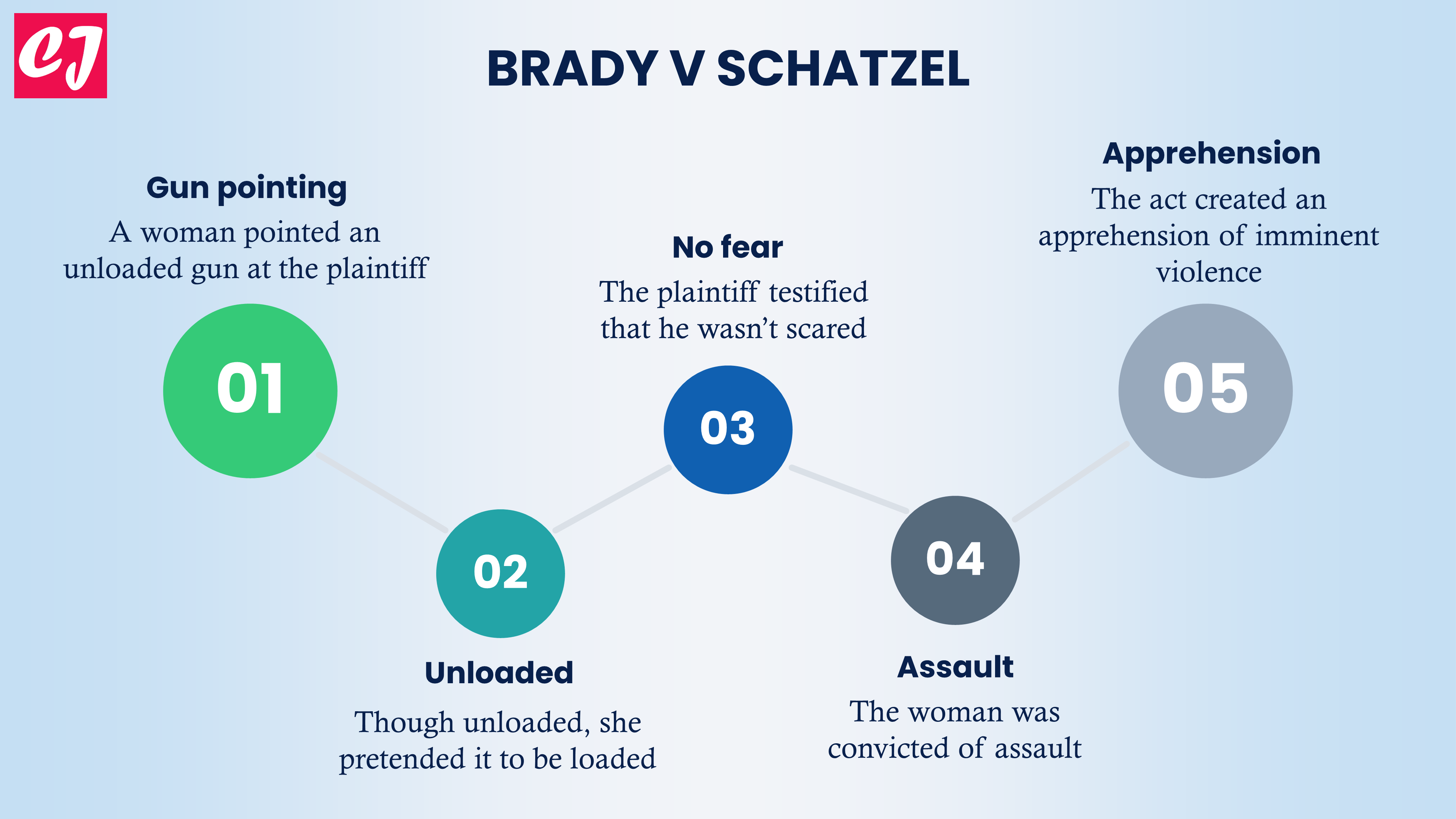

Case name & citation: Brady v Schatzel [1911] St R Qd 206 Case Overview Brady v Schatzel [1911] is a tort law case on assault.…

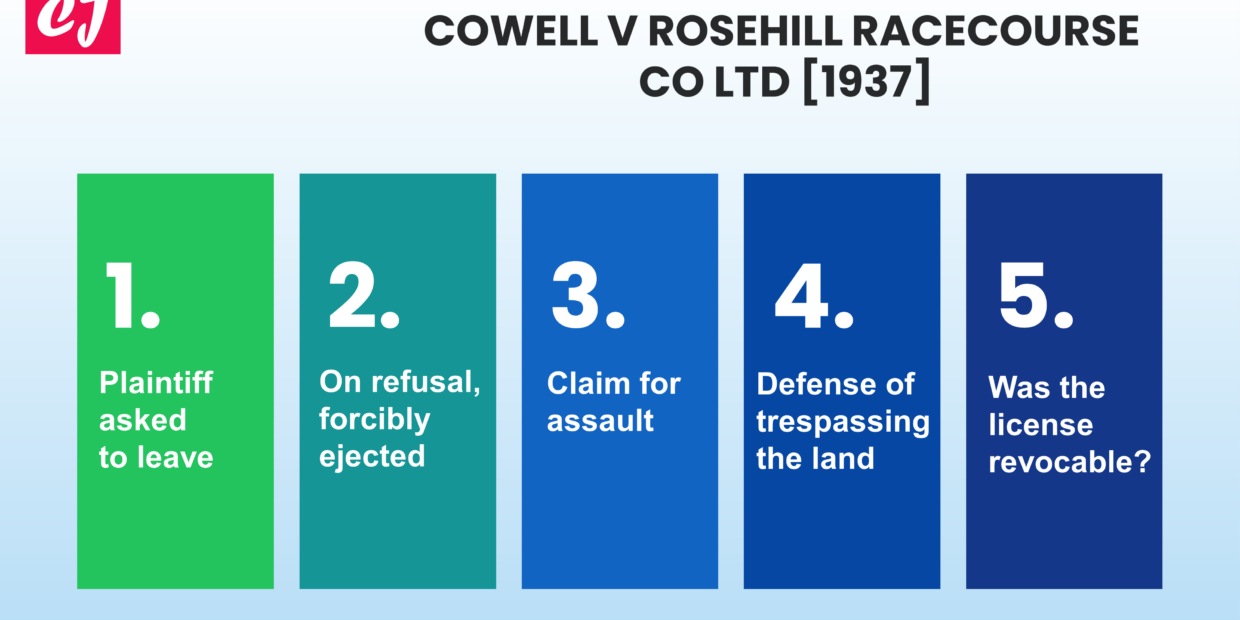

Cowell v Rosehill Racecourse Co Ltd [1937] is a tort law case from Australia differentiating between contractual rights and property rights. Case name & citation:…

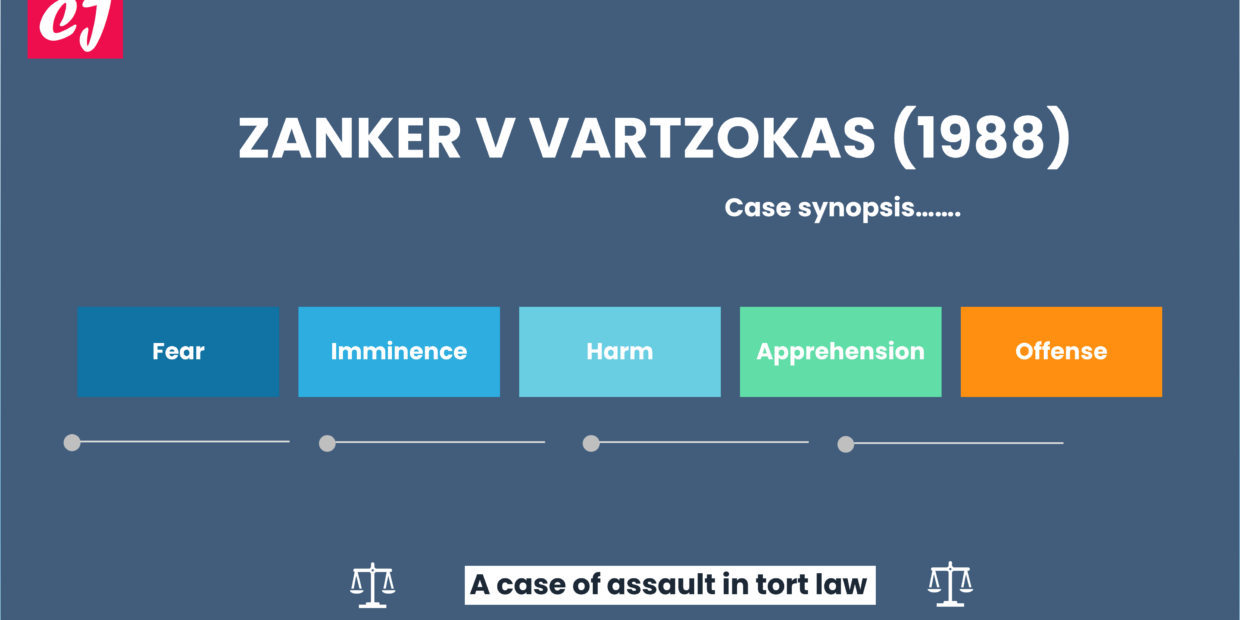

Case name & citation: Zanker v Vartzokas (1988) 34 A Crim R 11 Zanker v Vartzokas (1988) is a legal case that involved a potentially…

Rixon v Star City Pty Ltd [2001] is an Australian case on the issue of trespass to a person. It examined whether the touching of…

Rozsa v Samuels [1969] is an Australian case on the issue of assault. It examined whether a conditional threat might be sufficient to amount to…