Case name & citation: Ruxley Electronics and Construction Ltd v Forsyth [1996] AC 344; [1995] UKHL 8; [1995] 3 All ER 268 What is the…

Baltic Shipping Co v Dillon is an Australian contract law case that deals with a dramatic example of a tragically truncated holiday. The question arose…

Payzu v Saunders [1919] is a UK contract law case that concerned the question of awarding damages if the claimant fails to mitigate its losses.…

Chaplin v Hicks [1911] is a UK contract law case concerning the assessment of damages. It dealt with the issue of an actress losing her…

Howe v Teefy (1927) is an Australian contract law case that dealt with the issue of assessment of damages. Here, it was asked whether the…

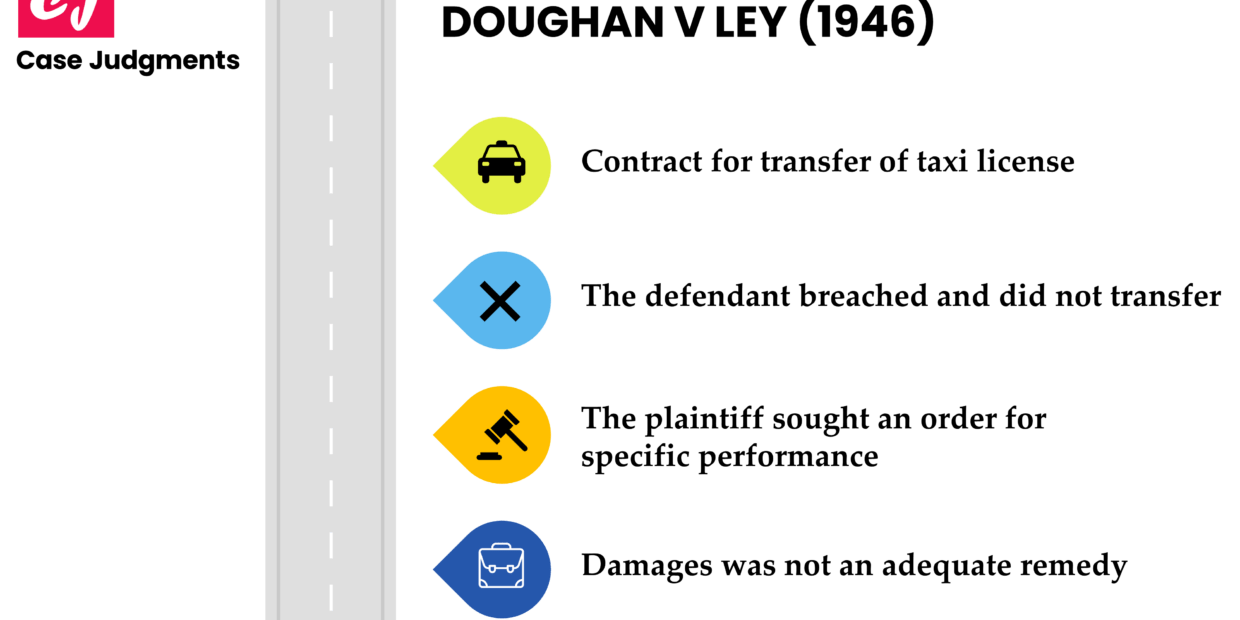

Dougan v Ley (1946) is an Australian case that throws light on the remedy of specific performance where there is a breach of contract. It…