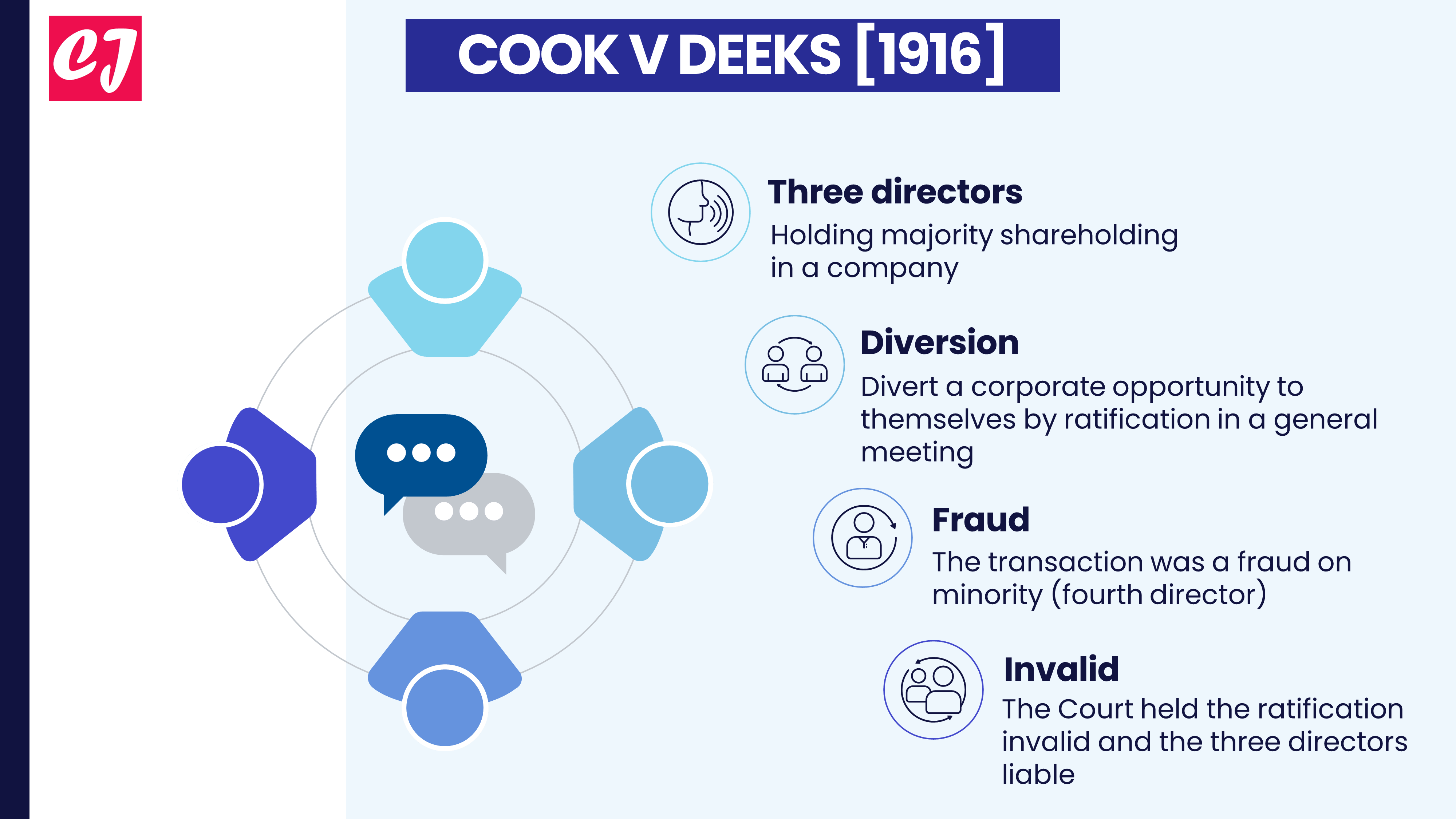

Cook v Deeks [1916] is a Canadian case that raised ethical and legal concerns over the actions taken by directors in a company. Case name…

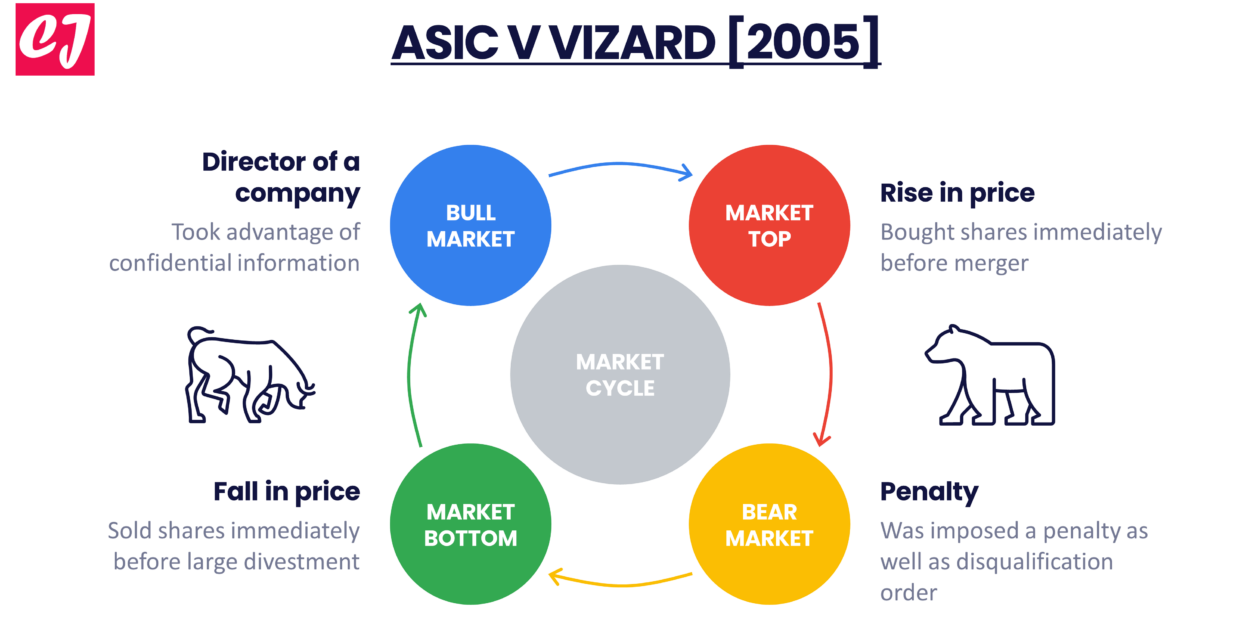

The case of ASIC v Vizard concerns a corporate offense committed by a director of a company. Case name & citation: Australian Securities and Investments…

Case name & citation: Hickman v Kent or Romney Marsh Sheep-Breeders’ Association [1915] 1 Ch 881 Court and jurisdiction: High Court, England and Wales The…

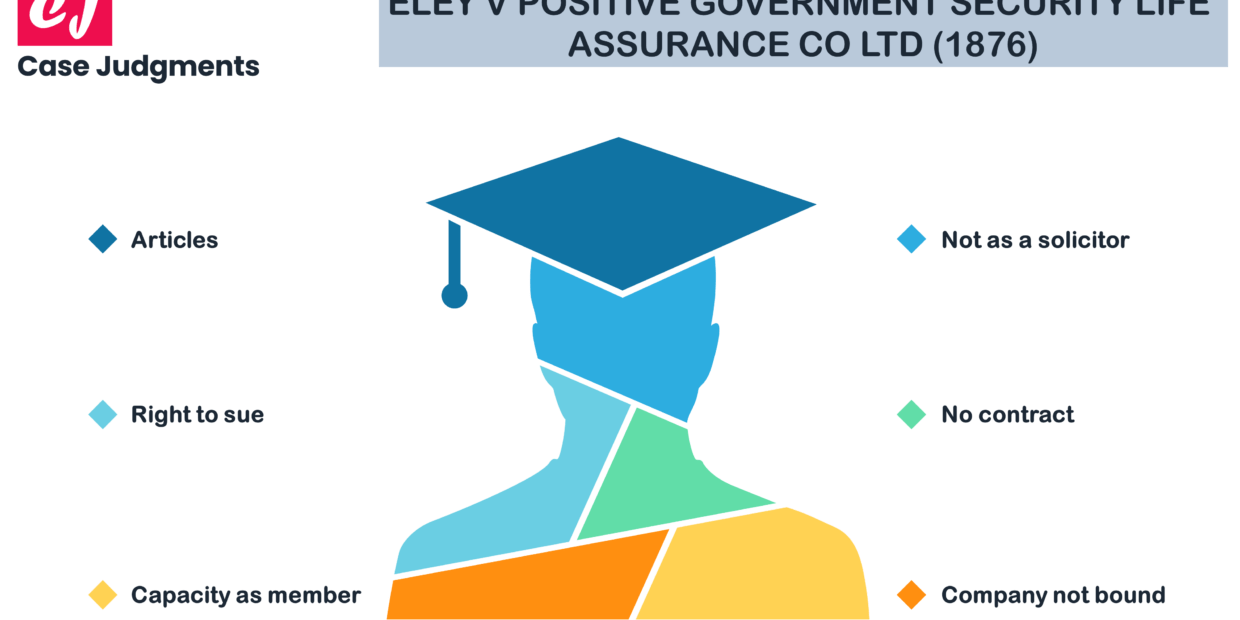

Eley v Positive Government Security Life Assurance Co Ltd (1876) is a UK company law case that dealt with the point that a company, by…

Case name & citation: DHN Food Distributors Ltd v Tower Hamlets London Borough Council [1976] 1 WLR 852 (CA) Court and jurisdiction: The Court of…

Case name & citation: Re Darby, ex parte Brougham [1911] 1 KB 95 Court and jurisdiction: High Court, UK Year of the case: 1911 The…

Case name & citation: Macaura v Northern Assurance Co Ltd [1925] AC 619 Court and jurisdiction: The House of Lords, England and Wales Decided on:…

Case name & citation: Gilford Motor Co Ltd v Horne [1933] All ER 109, [1933] Ch 935 Court and jurisdiction: Court of Appeal, England and…

Case name & citation: Jones v Lipman [1962] 1 W.L.R. 832 Court and jurisdiction: Chancery Division, United Kingdom Year of the case: 1962 The learned…