Sweeney v Boylan Nominees Pty Ltd [2006]: A Summary

Sweeney v Boylan Nominees Pty Ltd [2006] is a famous labour law case from Australia.

- Case name & citation: Sweeney v Boylan Nominees Pty Limited [2006] HCA 19; (2006) 227 ALR 46; (2006) 226 CLR 161

- The concerned Court: High Court of Australia

- Decided on: 16 May 2006

- Area of law: Employment status under labour law; Vicarious liability

Given below are the case facts.

Facts of the case (Sweeney v Boylan Nominees)

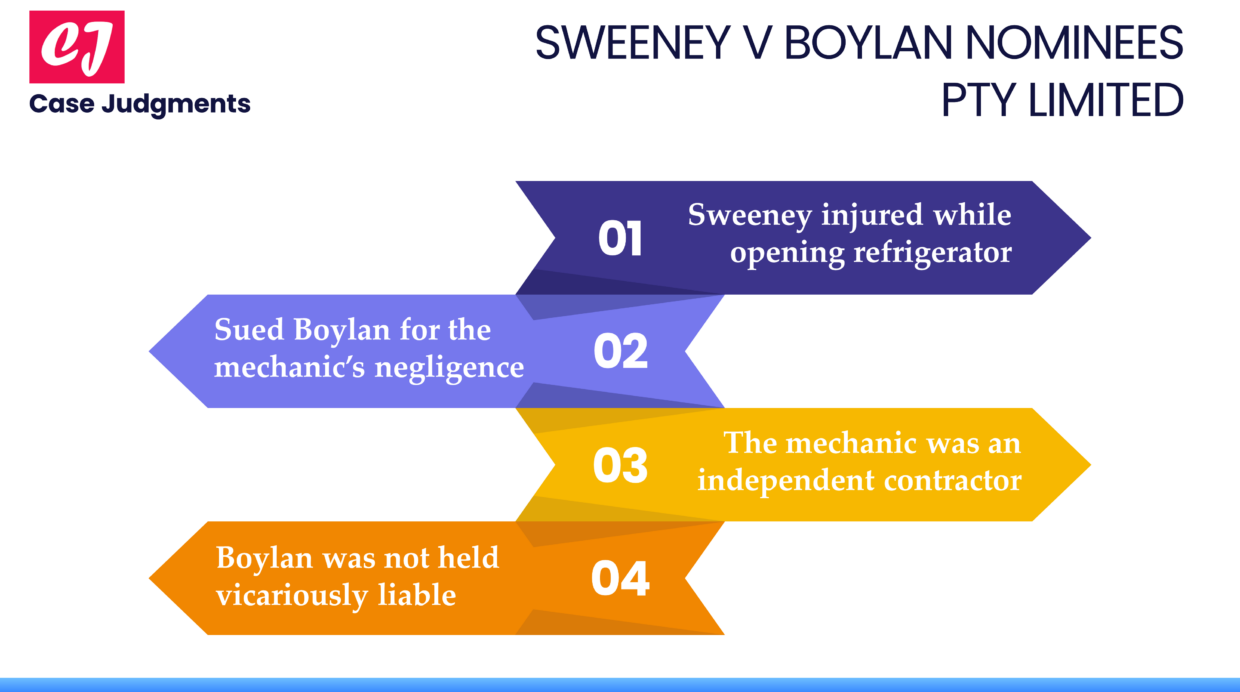

Mrs. Sweeney sustained injuries when a refrigerator door at a service station fell off and smacked her on the head. Earlier in the day on which Mrs. Sweeney was hurt, the owners of the service station had already informed Boylan, who owned the refrigerator, that there was a problem with the door. Mr. Comninos, a mechanic, was dispatched to the service station to undertake repairs. The trial judge determined that Mr. Comninos failed to exercise reasonable care, which resulted in Mrs. Sweeney’s injuries. This finding was not challenged on appeal.

Mrs. Sweeney filed a lawsuit against the owners of the service station and Boylan.

Issue that arose

The main issue of the case was the nature of Boylan’s engagement with Mr. Comninos. That is, whether he was an employee or an independent contractor.

Boylan had six employees in its service department, three field service employees who performed repairs at Boylan’s clients’ locations, and two contractors (including Mr. Comninos) who did the same work as the field service employees. Although Mr. Comninos worked for Boylan on a regular basis, the contractors were only required to work when the field service personnel were fully occupied. Mr. Comninos was referred to as “our mechanic” in Boylan’s service reports, and he was empowered to collect the amount due when repairs were finished. Boylan also referred to Mr. Comninos as “our mechanic” in a report to its public liability insurer.

Unlike the field service personnel, Mr. Comninos was not obligated to accept jobs from Boylan, wore no Boylan uniform, was not based on Boylan’s premises, and invoiced Boylan for the hours he worked. Mr. Comninos also possessed his own trade certificate and contractor’s license, as well as his own public liability and workers’ compensation insurance, and drove his own van with his own firm name on it.

Judgment of the Court in Sweeney v Boylan Nominees

Trial judge:

Mrs. Sweeney’s claim against the owners of the service station was dismissed in the District Court of New South Wales. And this claim was not pursued further on appeal. Mrs. Sweeney, on the other hand, prevailed in her case against Boylan on the grounds that it was vicariously liable for the negligence of Mr. Comninos. The trial judge determined that the mechanic was acting as a servant or agent of Boylan, and he had the approval and authority from Boylan to carry out the work in question. In reaching this, the trial judge gave significant weight to the various documents that referred to Mr. Comninos as “our mechanic.”

Court of Appeal:

The New South Wales Court of Appeal overturned the trial judge’s decision and ruled that the relationship between Boylan and the mechanic, Mr. Comninos, was not that of an employment relationship. The Court of Appeal cited several reasons to support this finding:

- Boylan did not exert control over Mr. Comninos in his day-to-day work activities.

- There was no mutual obligation between Boylan and Mr. Comninos to provide and accept work.

- Mr. Comninos conducted his work under his own name.

- Mr. Comninos supplied his own equipment and tools for the tasks and bought his own spare parts.

- Boylan paid Mr. Comninos based on a piecework basis.

- Mr. Comninos issued his own invoices to Boylan.

- Mr. Comninos provided his own insurance coverage and managed his superannuation.

All of these factors distinguished his independence from Boylan’s direct employment. This indicated that he was an independent contractor and not an employee.

High Court:

The High Court upheld the decision of the New South Wales Court of Appeal.

The majority underlined the importance of distinguishing between employees and independent contractors in determining the scope of vicarious liability. It moved away from relying solely on the control test and preferred to consider the totality of the relationship between the parties as articulated in Hollis v Vabu Pty Ltd (2001).

The Court accepted that the facts did not support a finding that Mr. Comninos was an employee. Therefore, Boylan was not held vicariously liable for Mr. Comninos’ actions, and Mrs. Sweeney’s claim against Boylan was not upheld based on vicarious liability.

List of references:

- http://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/SydLawRw/2007/5.pdf

- https://doylesconstructionlawyers.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Sweeney-v-Boylan-Nominees.pdf

You might also like:

More from labour law: