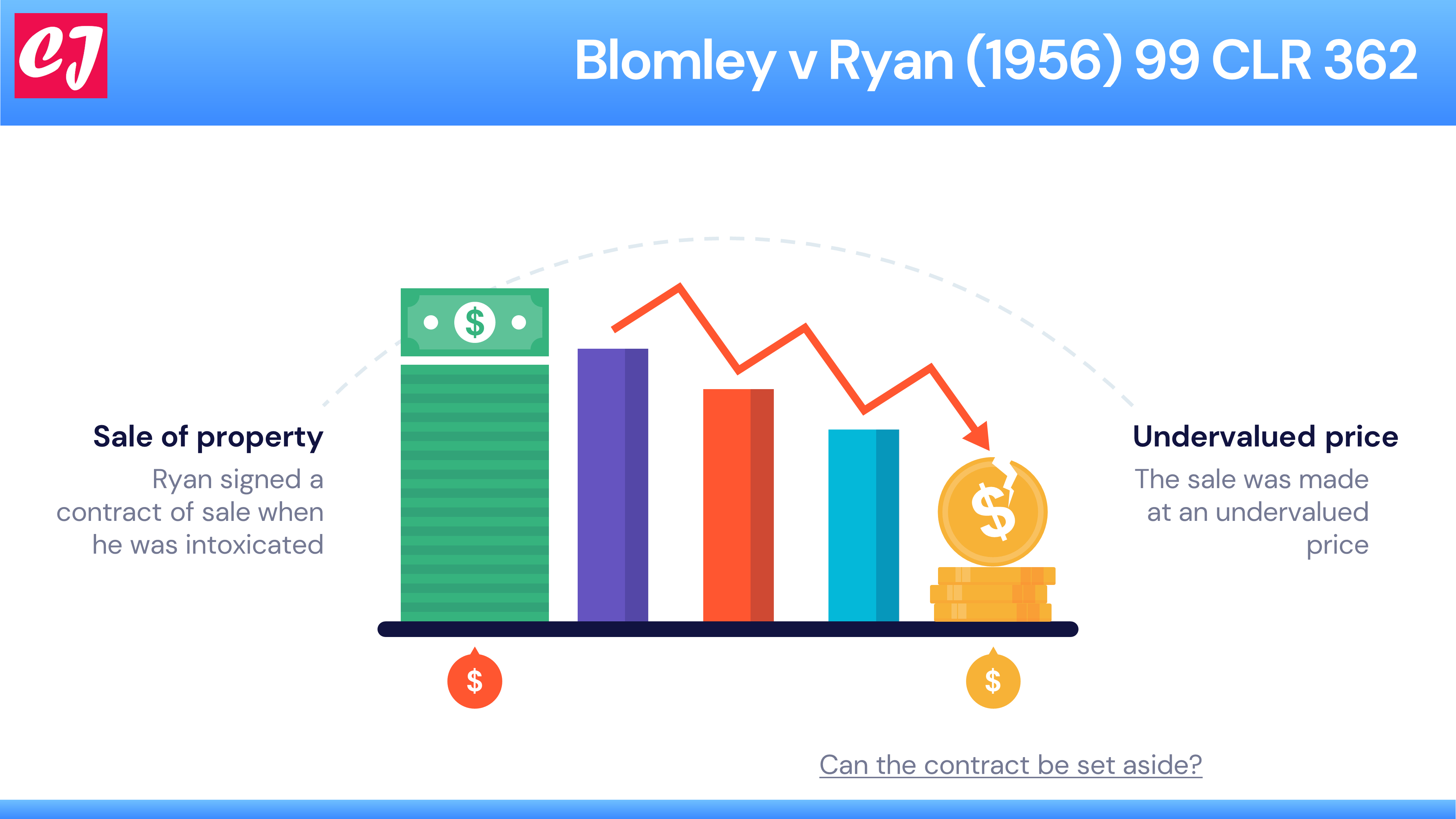

Case name & citation: Blomley v Ryan (1956) 99 CLR 362; [1956] HCA 81 Blomley v Ryan (1956) is a contract law case concerning a…

Case name & citation: Commercial Bank of Australia Ltd v Amadio [1983] HCA 14; (1983) 151 CLR 447 This is one of the leading cases…