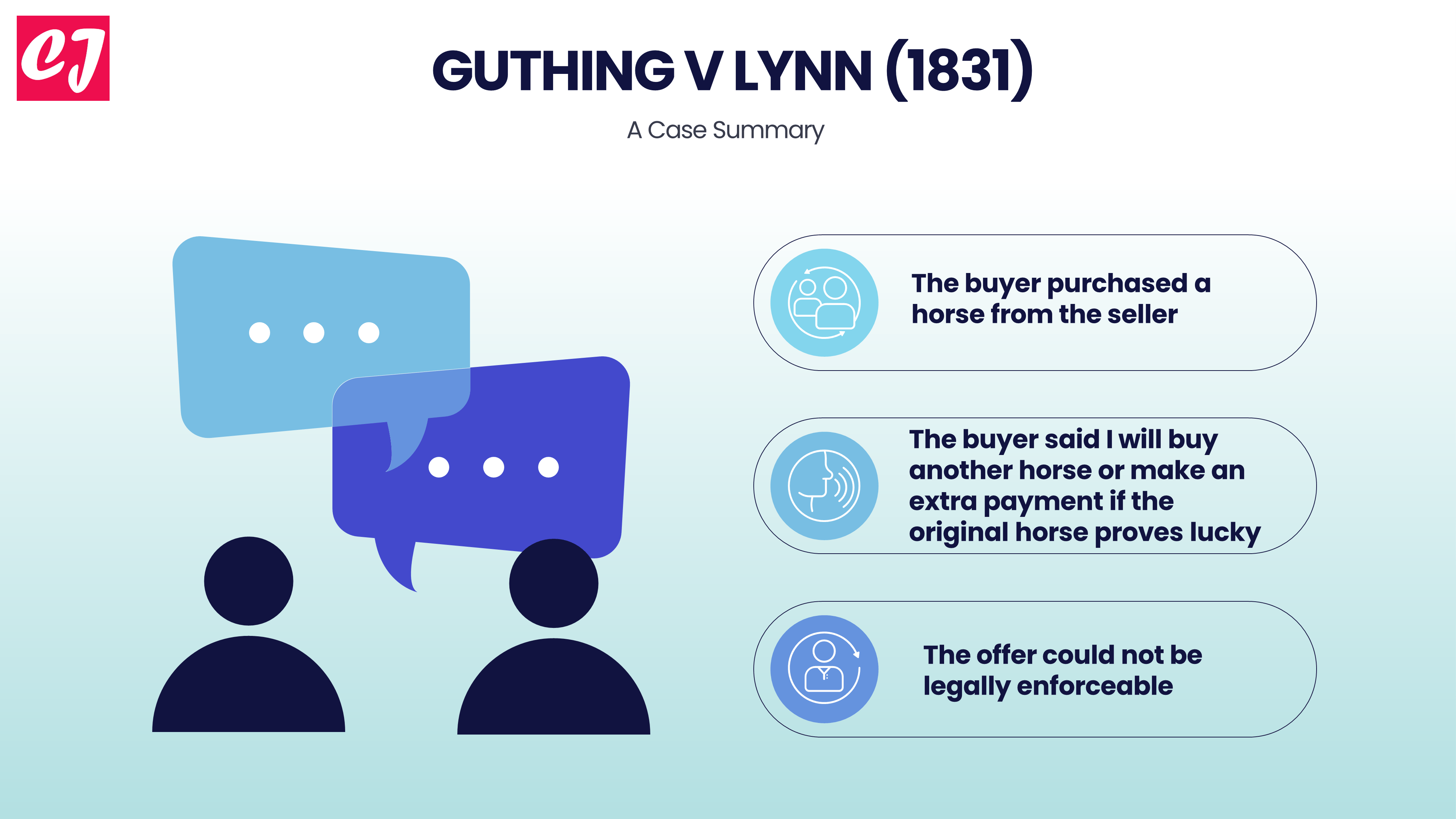

Case name & citation: Guthing v Lynn (1831) 2 B & Ad 232 Guthing v Lynn (1831) is a contract law case on issues of…

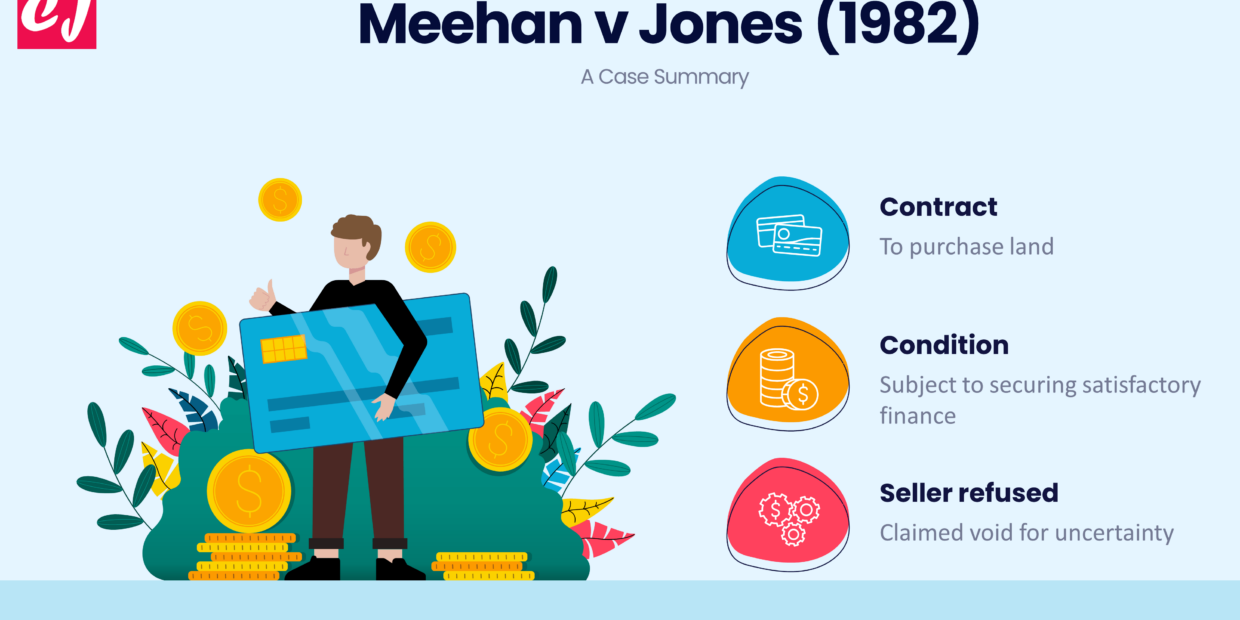

Case name & citation: Meehan v Jones [1982] HCA 52; (1982) 149 CLR 571 What is the case about? Meehan v Jones (1982) is a…

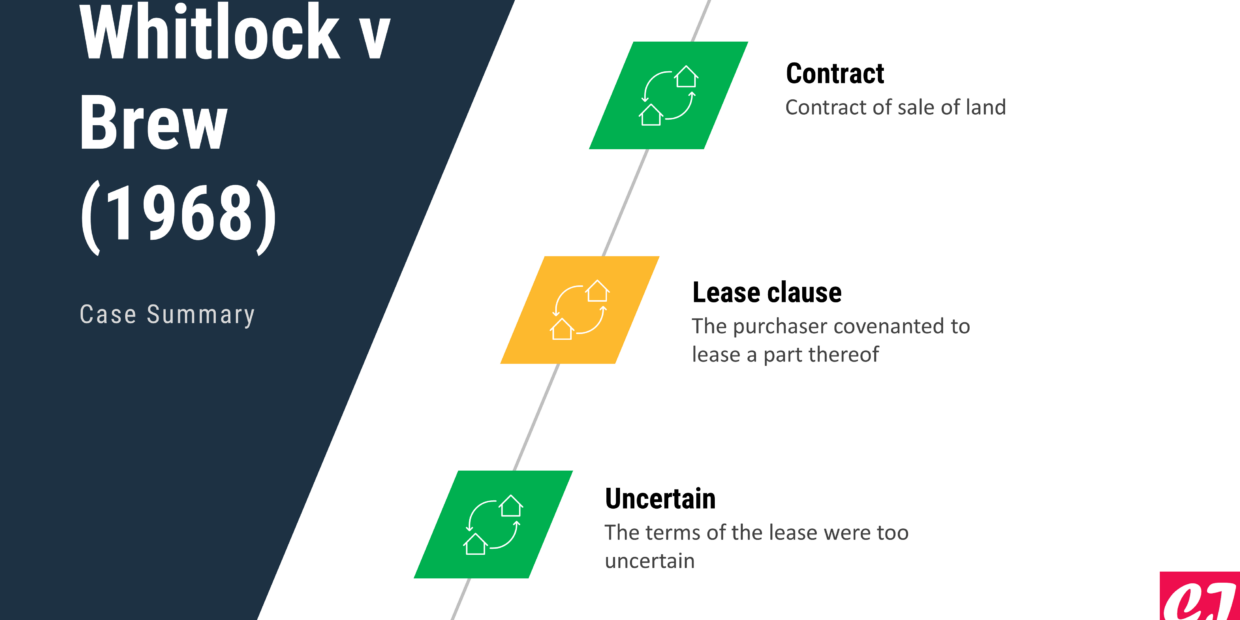

Whitlock v Brew (1968) revolves around the issue of uncertainty and whether a clause of a contract that is uncertain can render the whole contract…