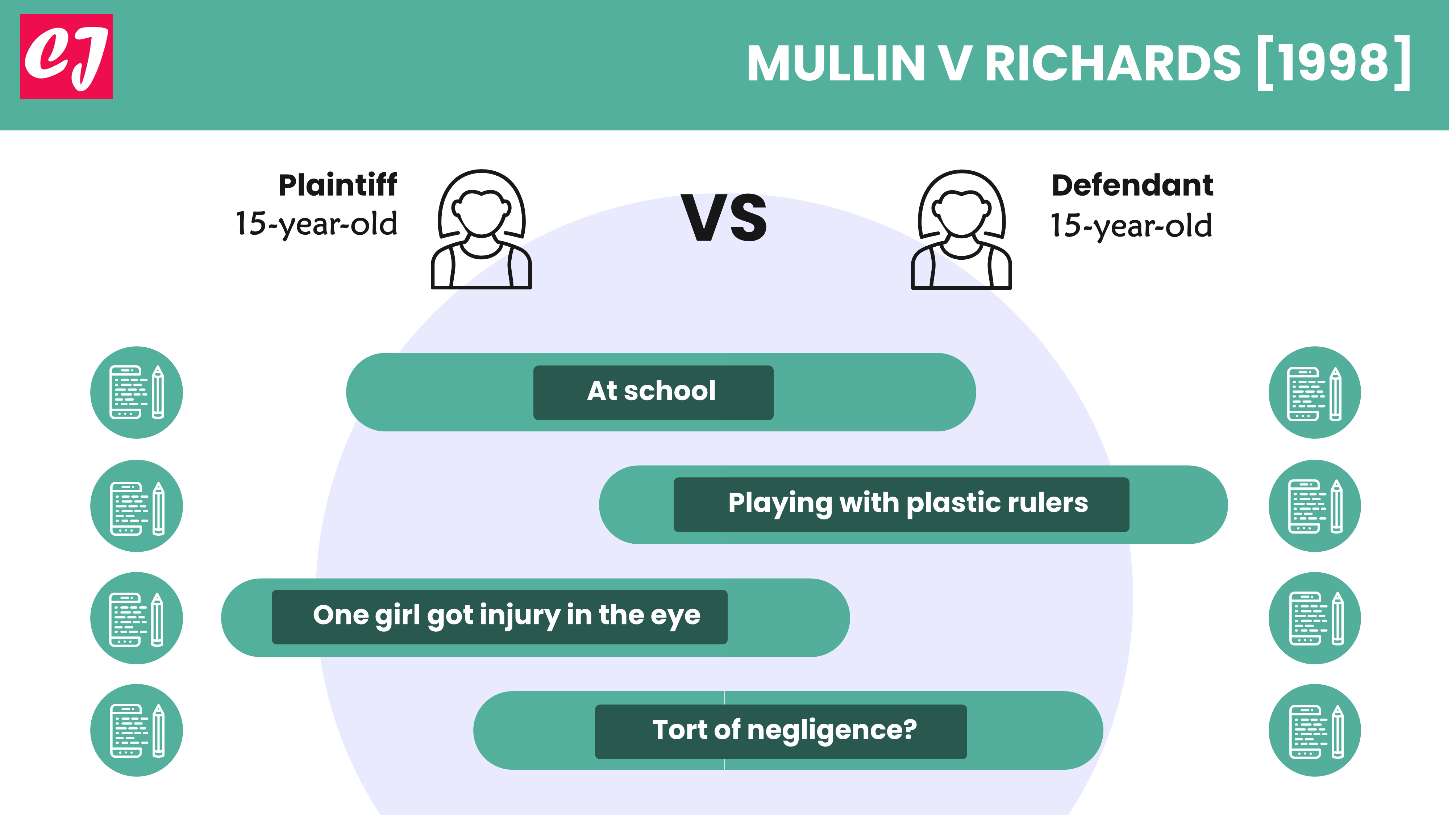

Case name & citation: Mullin v Richards [1998] 1 WLR 1304; [1998] 1 ALL ER 920 Case Overview This is a tort law case on…

Case name & citation: Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd v Zaluzna [1987] HCA 7; (1987) 162 CLR 479 This case is a famous case from…

Romeo v Conservation Commission of the Northern Territory (1998) is a widely recognized case from Australia. It concerns a negligence claim against the Conservation Commission…

Doubleday v Kelly [2005] is a tort law case concerning the foreseeability of risk and duty of care. Given below are the case details: Case…

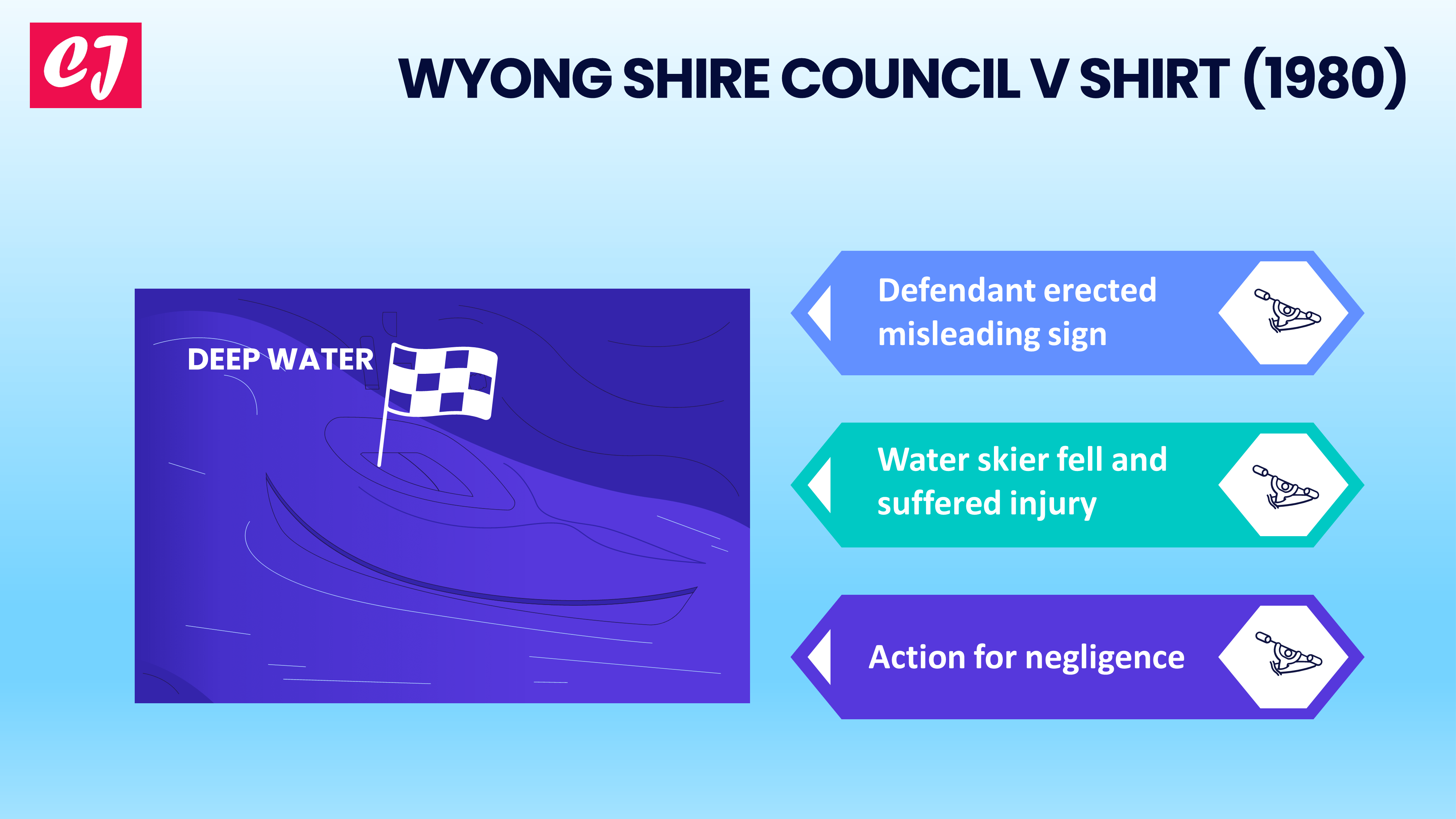

The case of Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (1980) addressed the topic of negligence and whether a Council was irresponsible in placing a sign indicating…

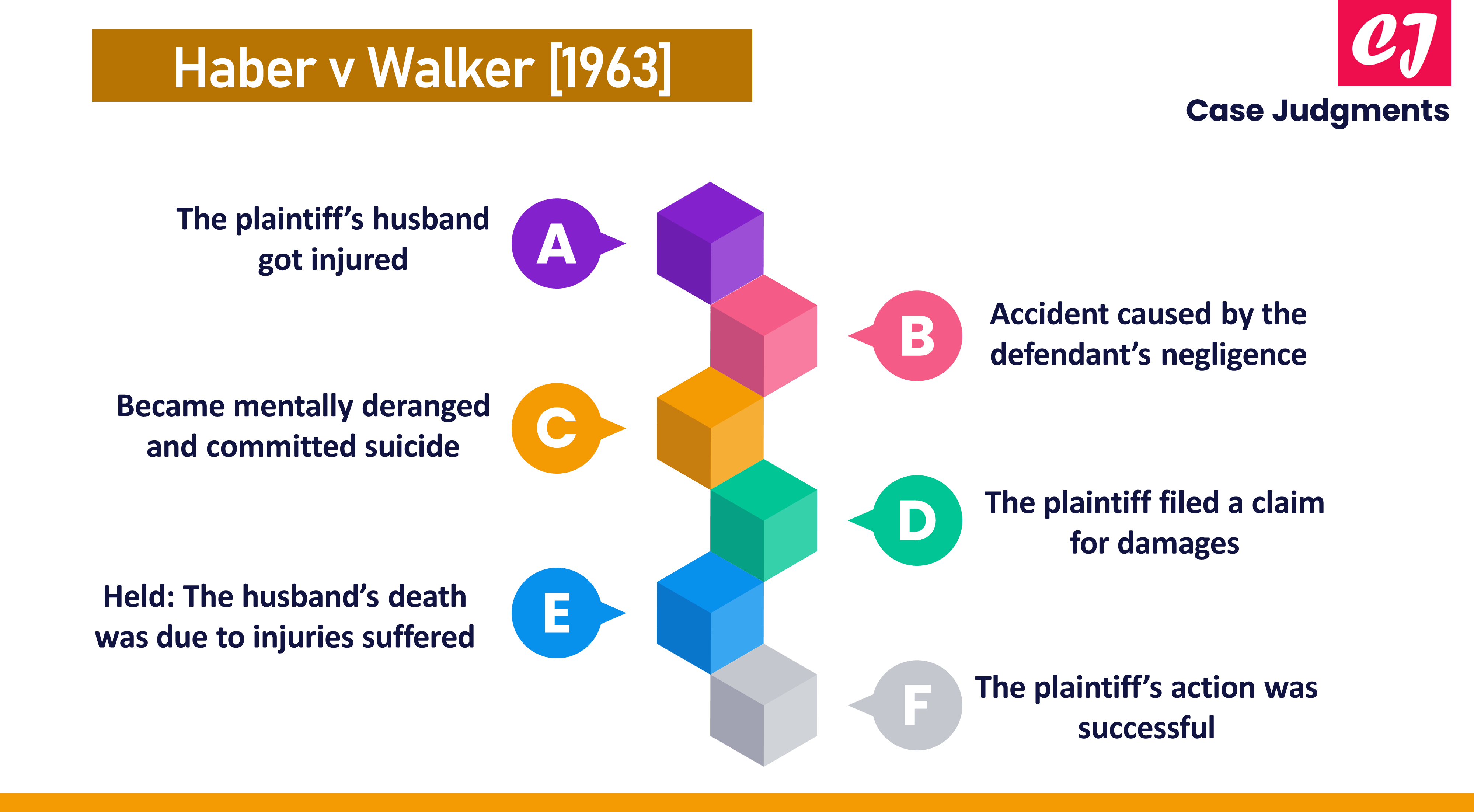

Haber v Walker [1963] is a tort law case on issues related to causation, foreseeability and novus actus interveniens. Here, as a result of the…