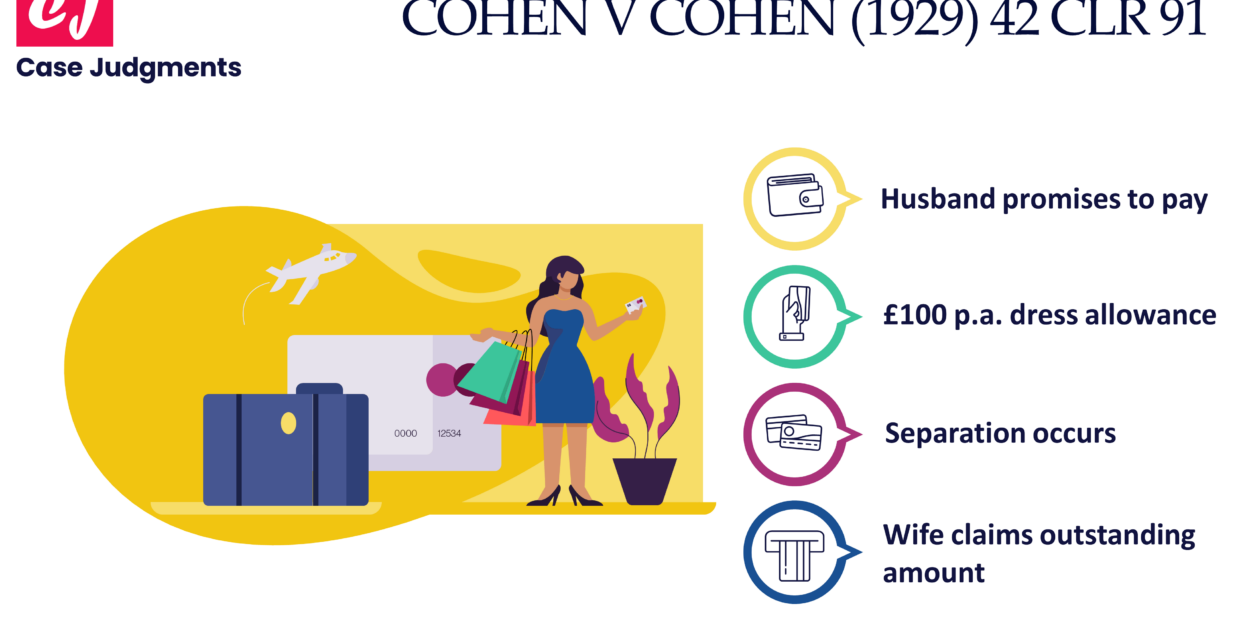

Cohen v Cohen (1929) is a contract law case from Australia that revolved around a dispute between a married couple, Mr. Cohen and Mrs. Cohen.…

Case name & citation: Ermogenous v Greek Orthodox Community of SA Inc [2002] HCA 8; (2002) 209 CLR 95 What is the case about? Agreements…