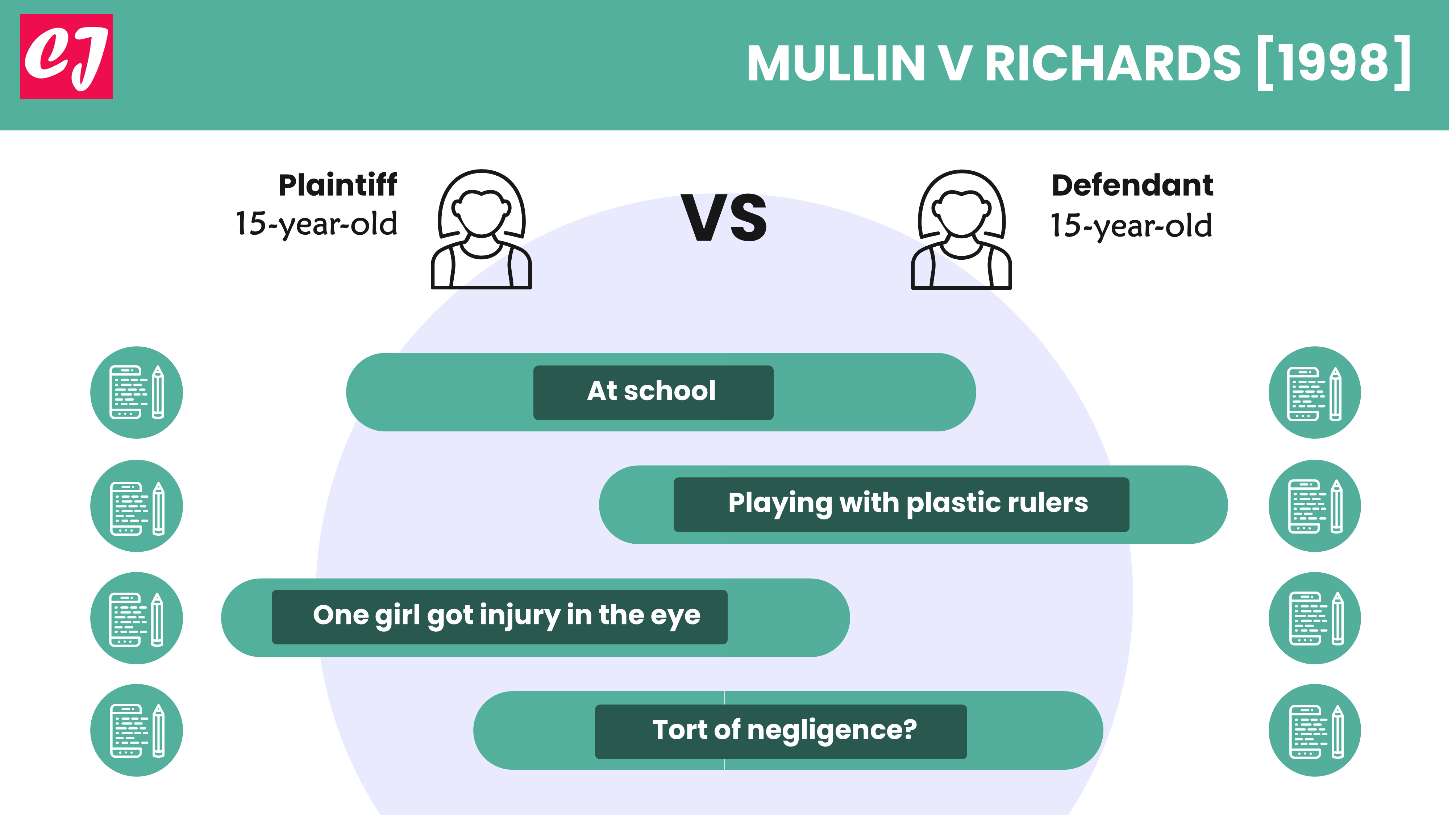

Case name & citation: Mullin v Richards [1998] 1 WLR 1304; [1998] 1 ALL ER 920 Case Overview This is a tort law case on…

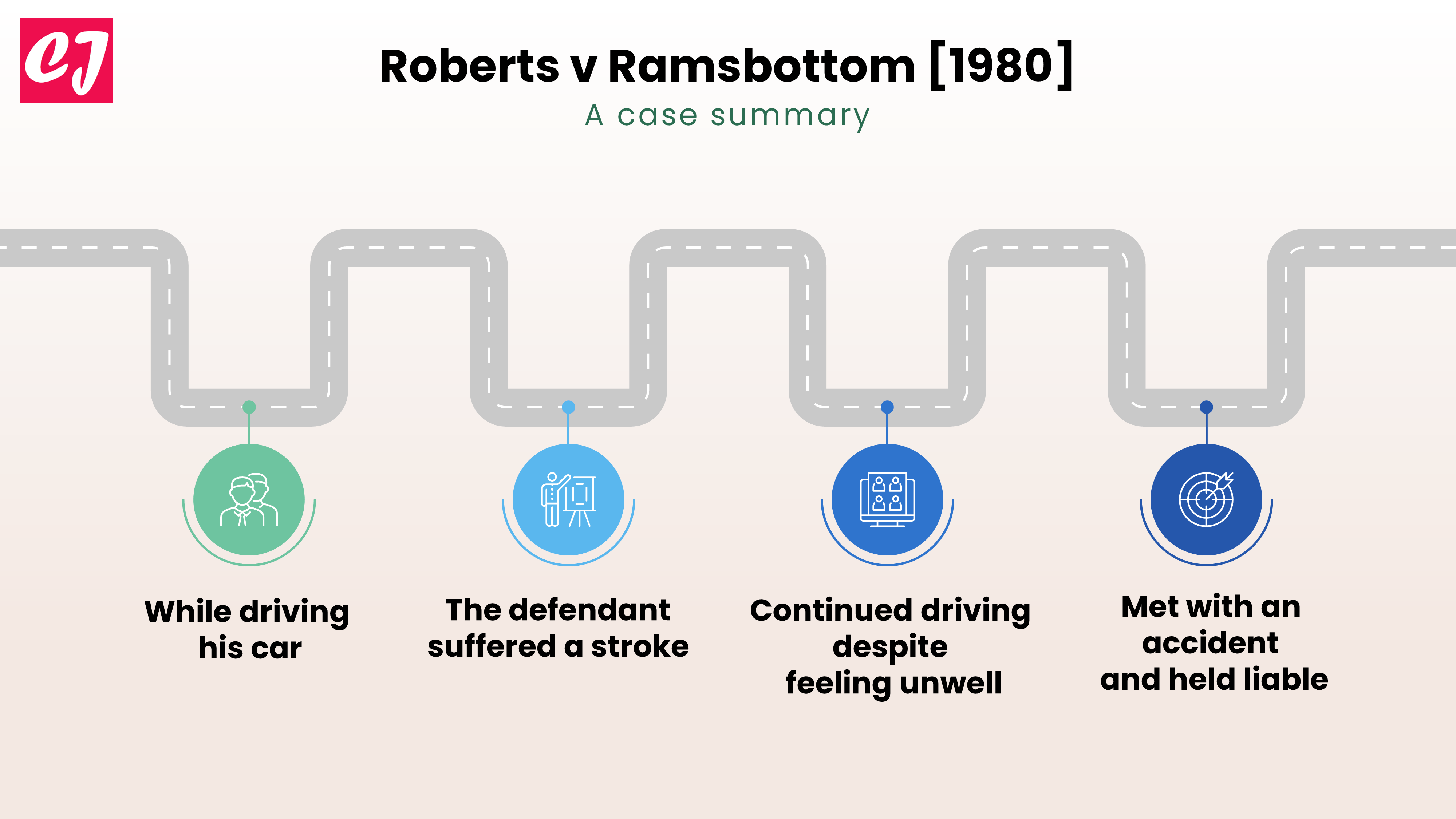

Case name & citation: Roberts v Ramsbottom [1980] 1 WLR 823; [1980] 1 All ER 7 Jurisdiction: England and Wales The learned judge: Neill J.…

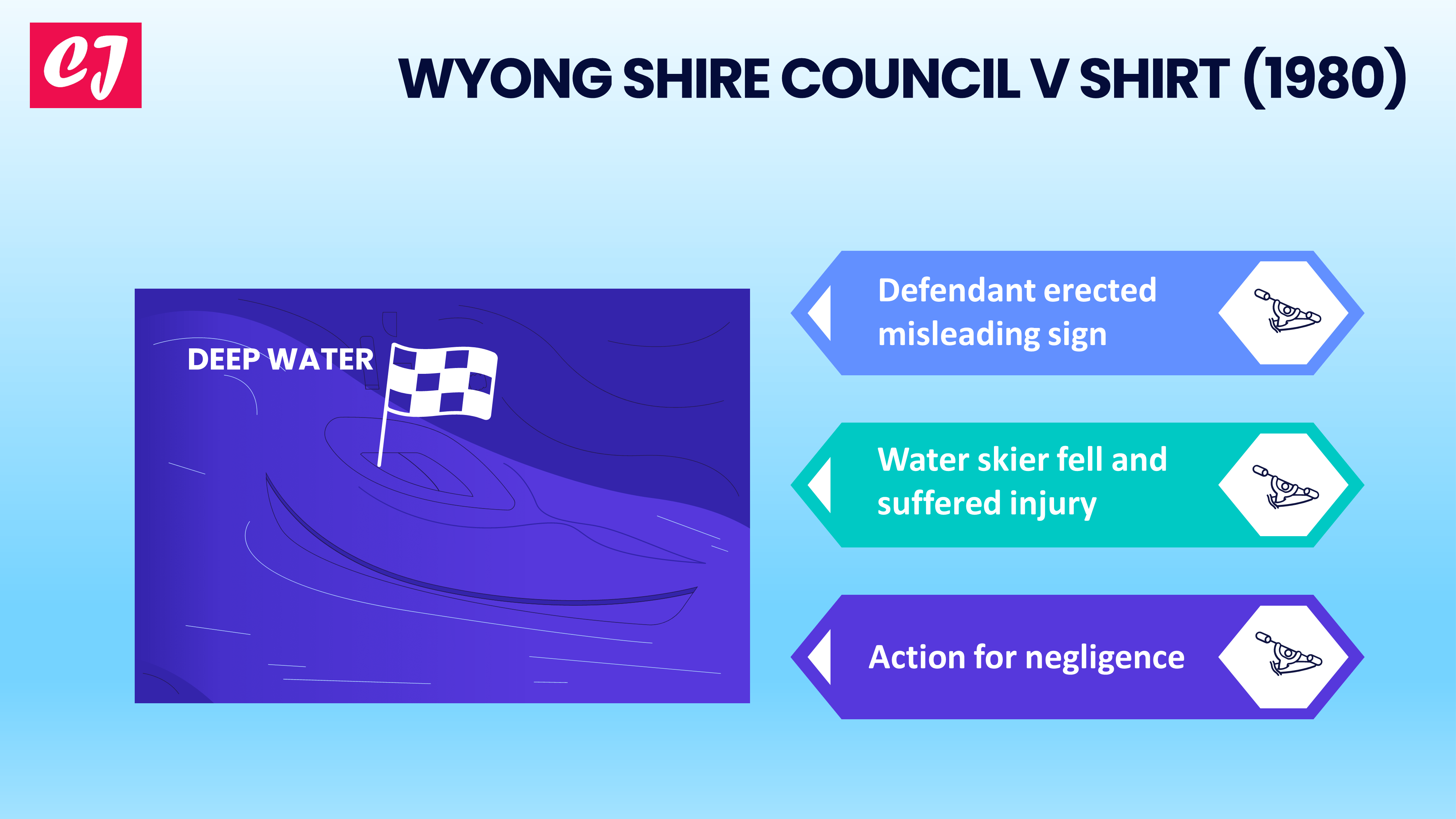

The case of Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (1980) addressed the topic of negligence and whether a Council was irresponsible in placing a sign indicating…

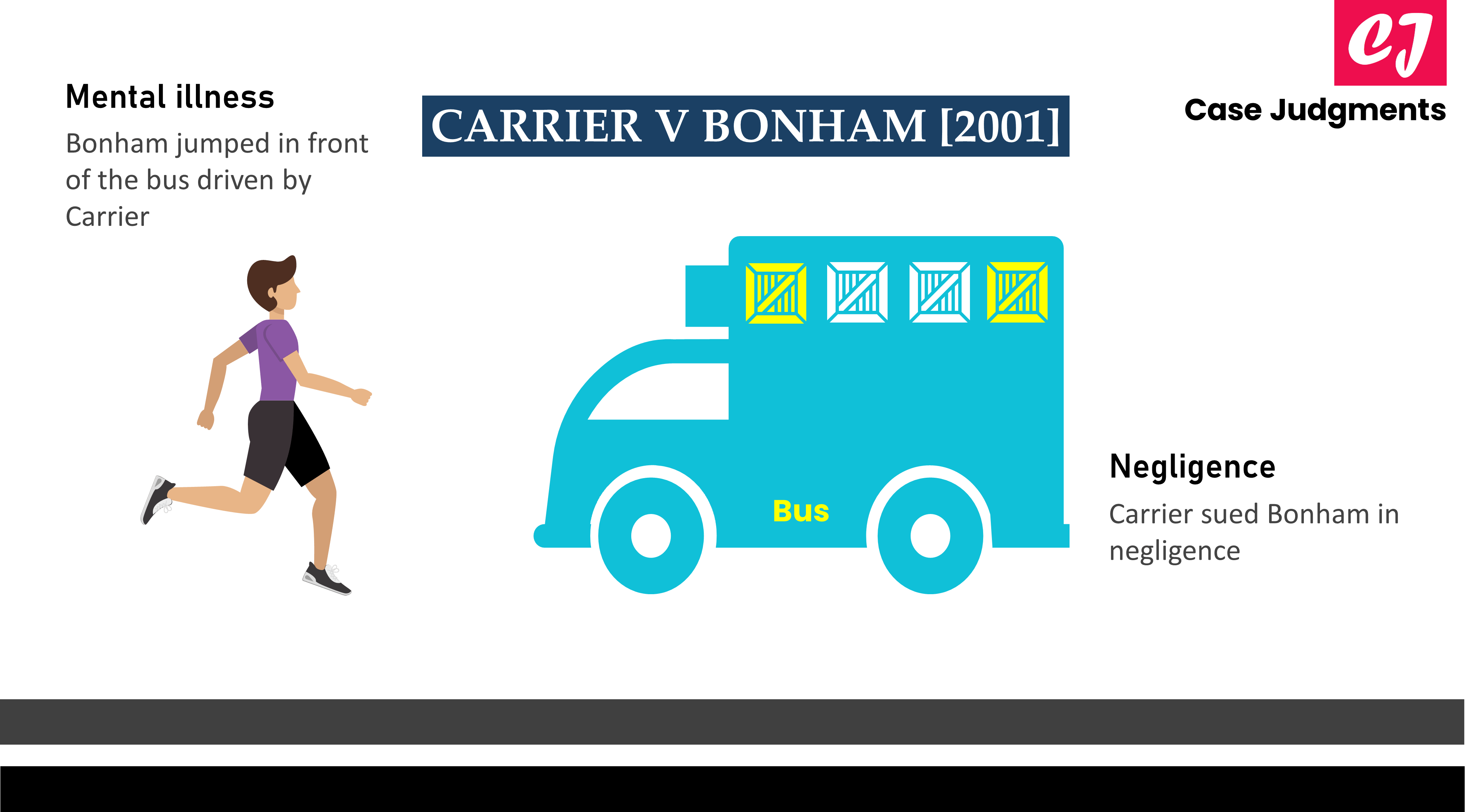

Carrier v Bonham [2001] is a classic tort law case that deals with the liability of mentally ill individuals for negligence issues. The case discusses…