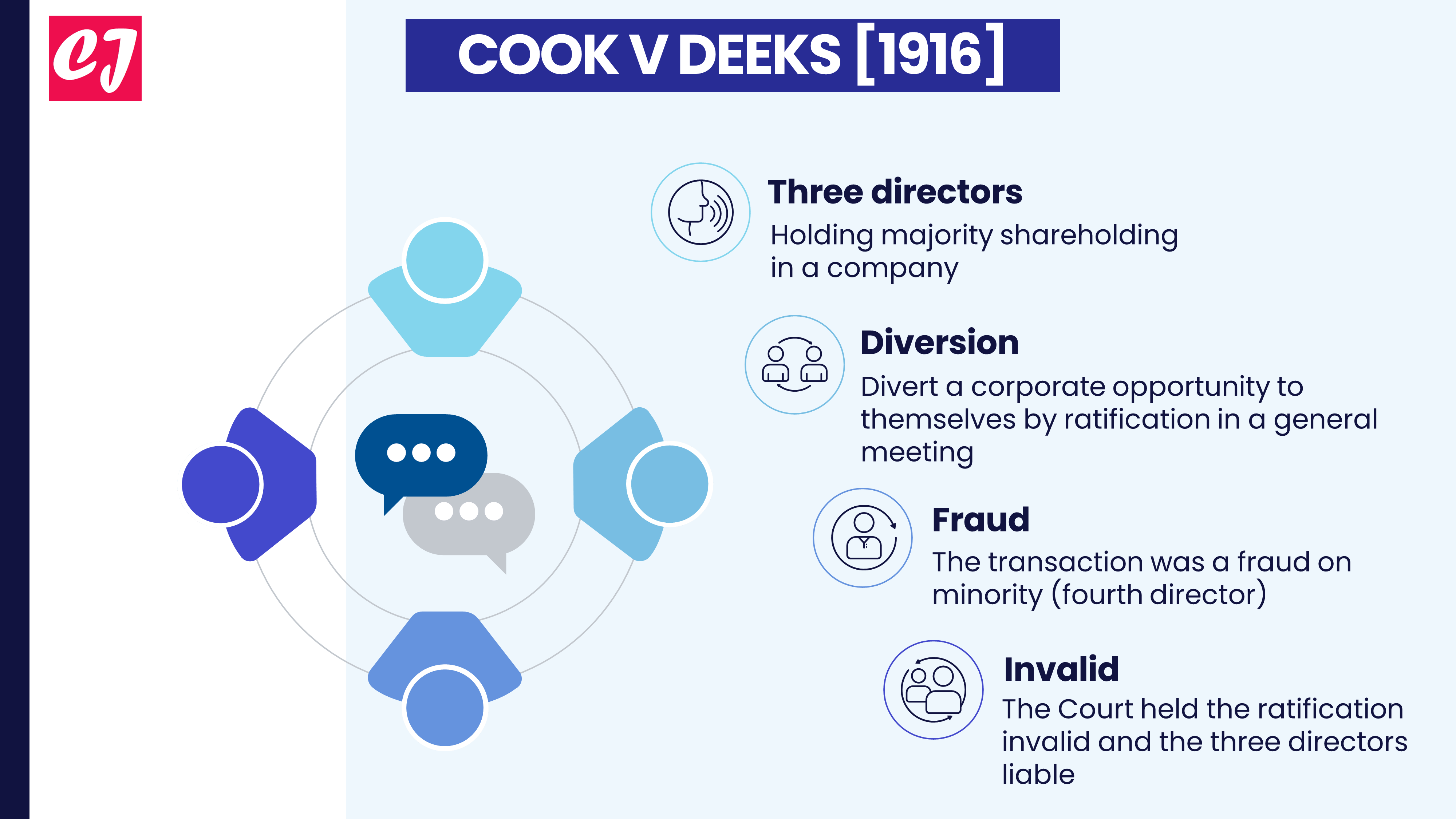

Cook v Deeks [1916] is a Canadian case that raised ethical and legal concerns over the actions taken by directors in a company. Case name…

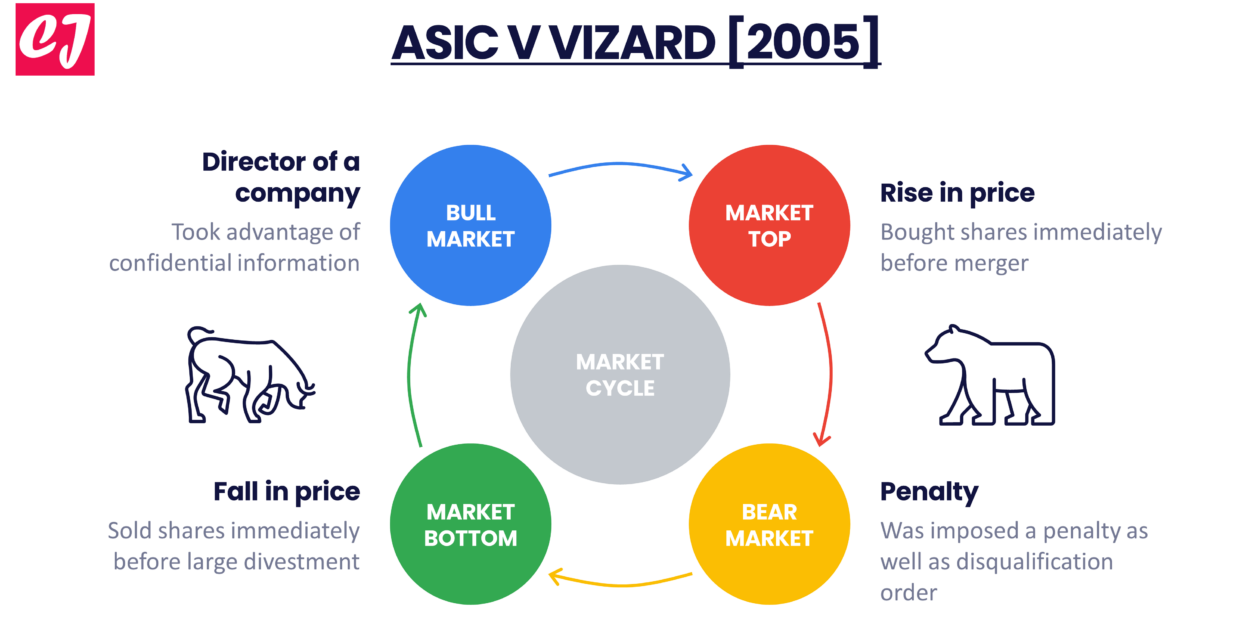

The case of ASIC v Vizard concerns a corporate offense committed by a director of a company. Case name & citation: Australian Securities and Investments…