Case name & citation: Varley v Whipp [1900] 1 QB 513 Year of the case: 1900 Jurisdiction: England and Wales Area of law: Sale by…

Case name & citation: Baldry v Marshall [1925] 1 KB 260 What is the case about? This is a famous case concerning the implied condition…

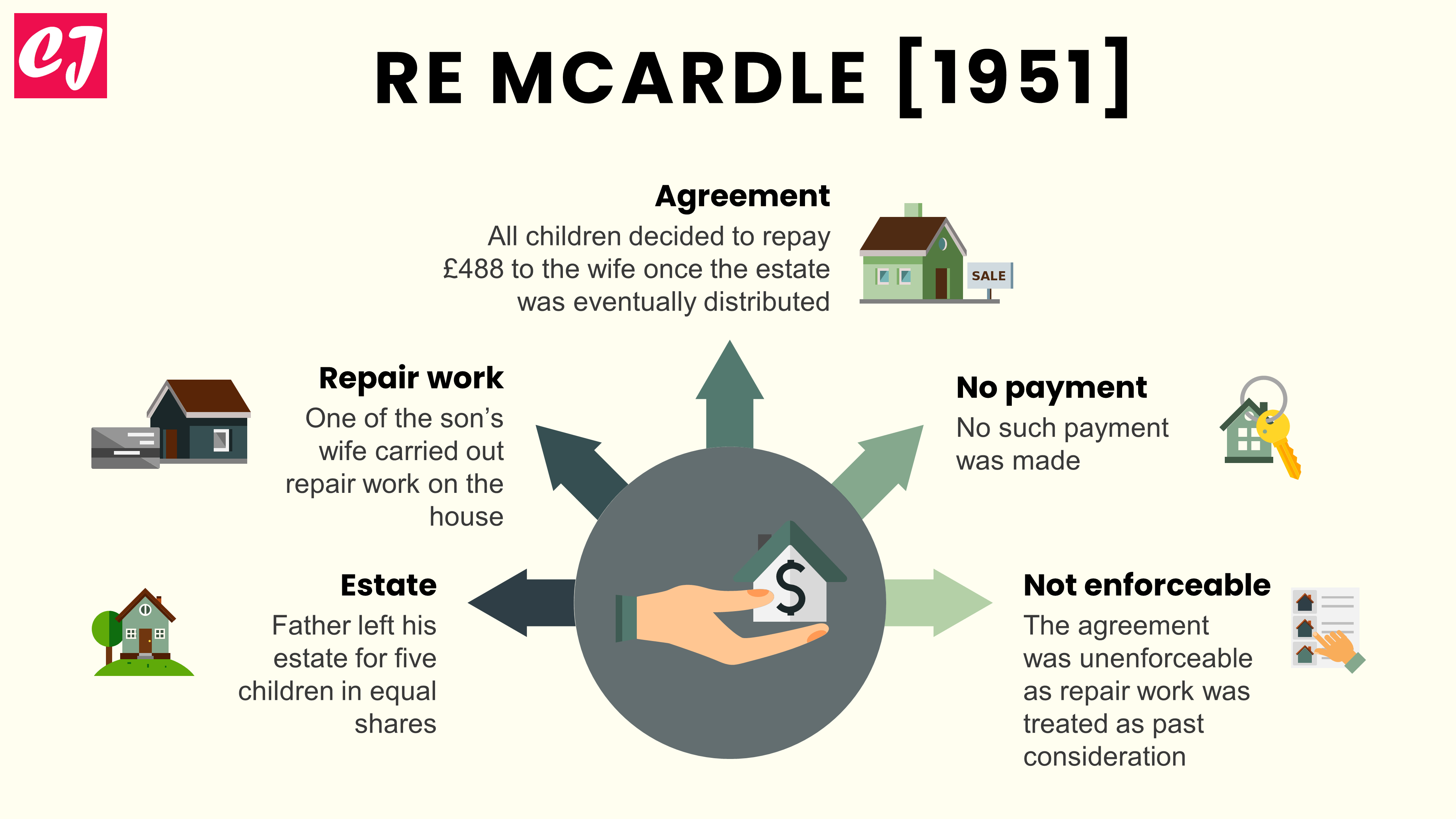

Case name & citation: Re McArdle [1951] Ch 669; [1951] 1 All ER 905 Court and jurisdiction: Court of Appeal; England and Wales Area of…

Case name & citation: Rowland v Divall [1923] 2 KB 500 CA Rowland v Divall is a case throwing light on the rights of a…

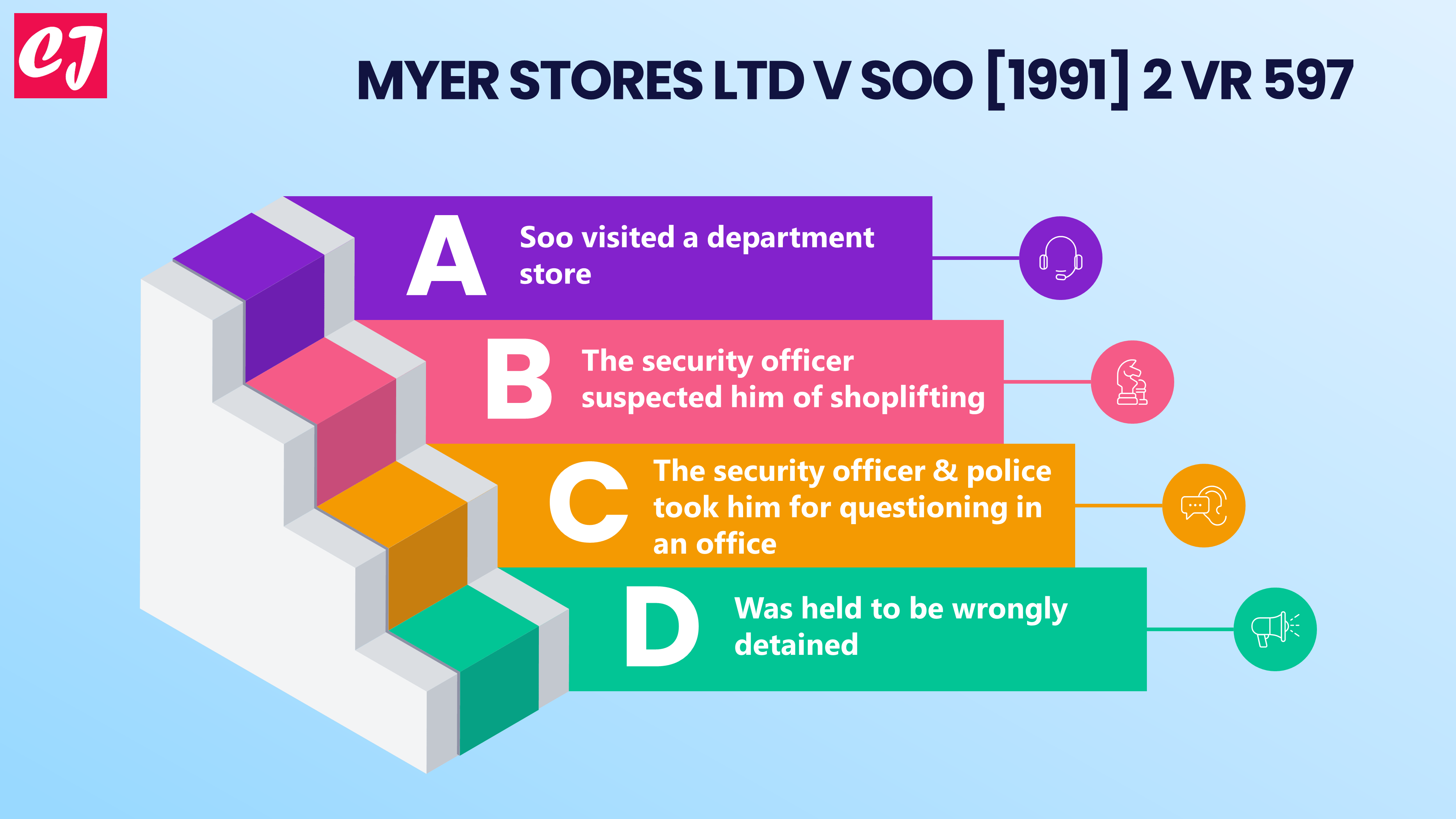

Myer Stores Ltd v Soo [1991] is an Australian tort law case concerning the detainment of a customer at a departmental store. The question arose…

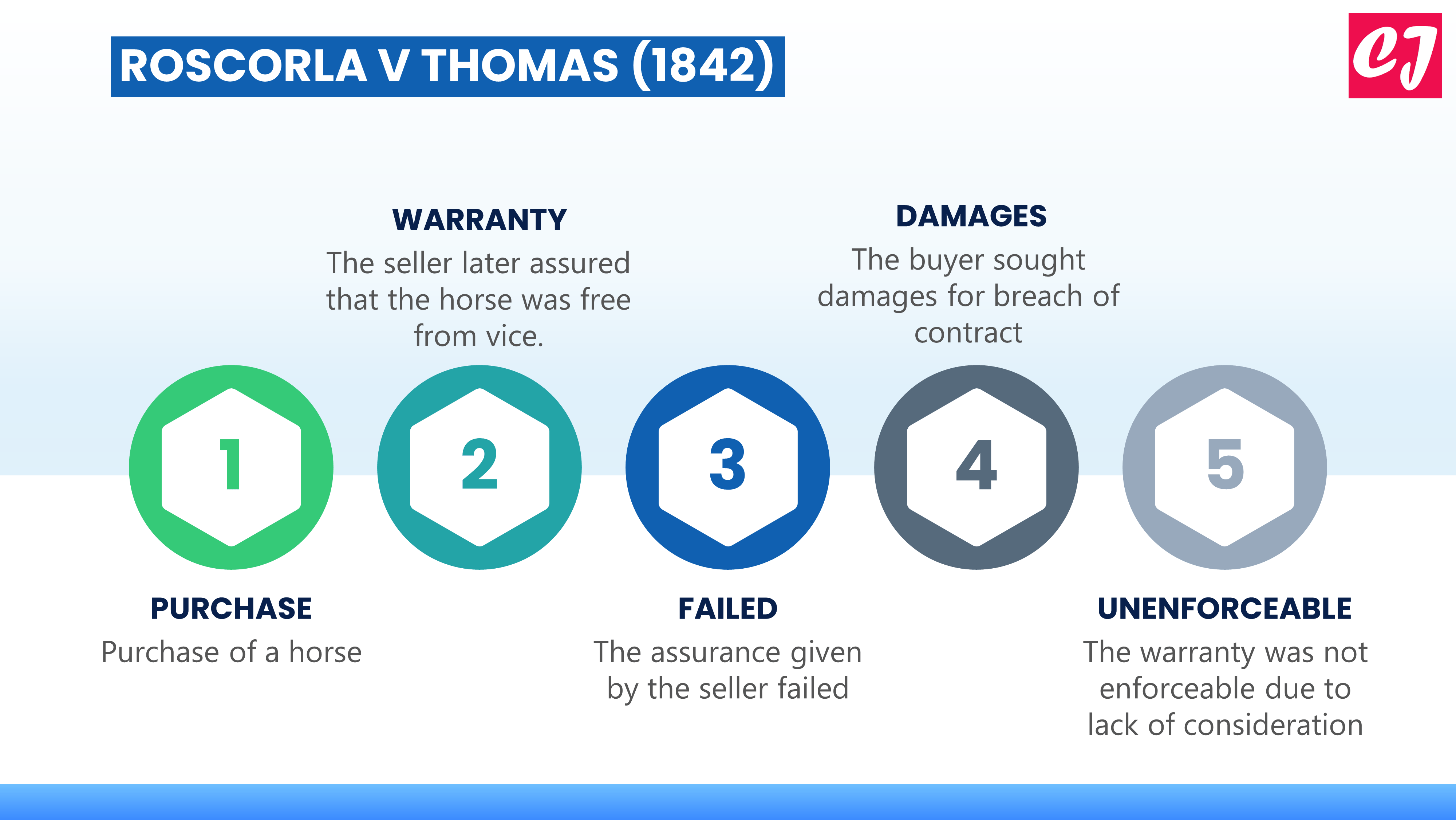

Case name & citation: Roscorla v Thomas (1842) 3 QB 234; [1842] EWHC QB J74; (1842) 114 ER 496 A Quick Summary Roscorla v Thomas…

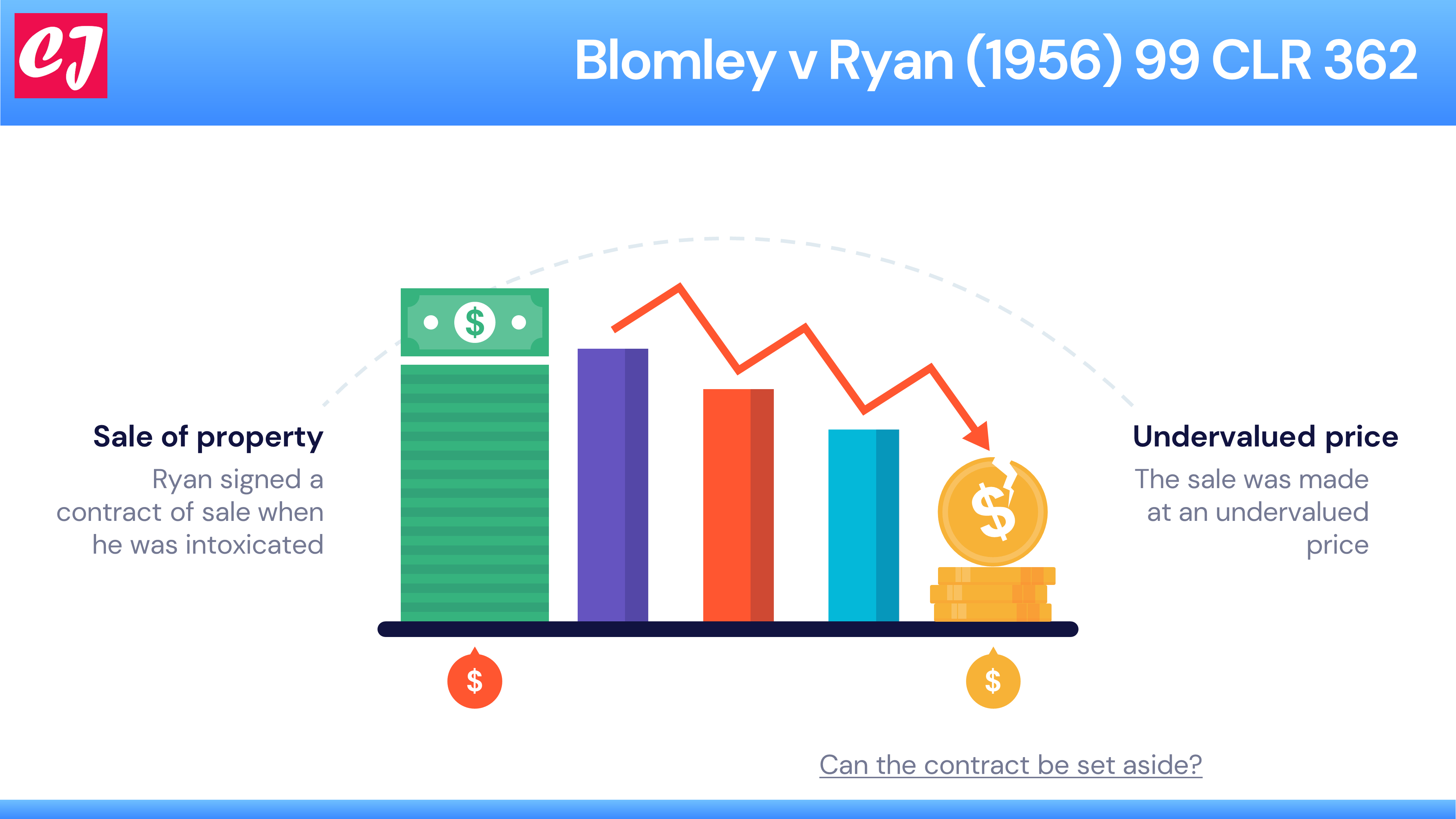

Case name & citation: Blomley v Ryan (1956) 99 CLR 362; [1956] HCA 81 Blomley v Ryan (1956) is a contract law case concerning a…

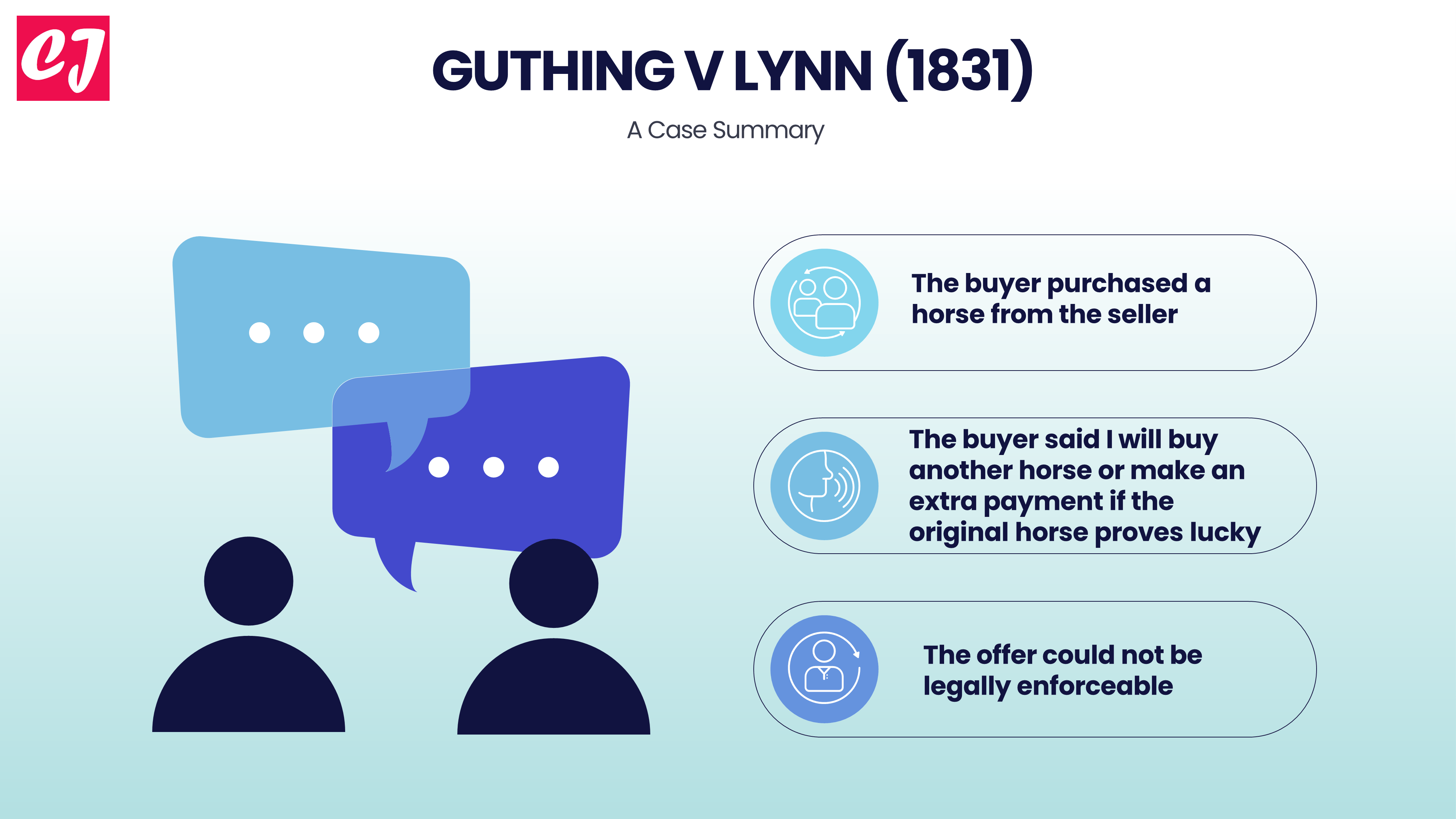

Case name & citation: Guthing v Lynn (1831) 2 B & Ad 232 Guthing v Lynn (1831) is a contract law case on issues of…

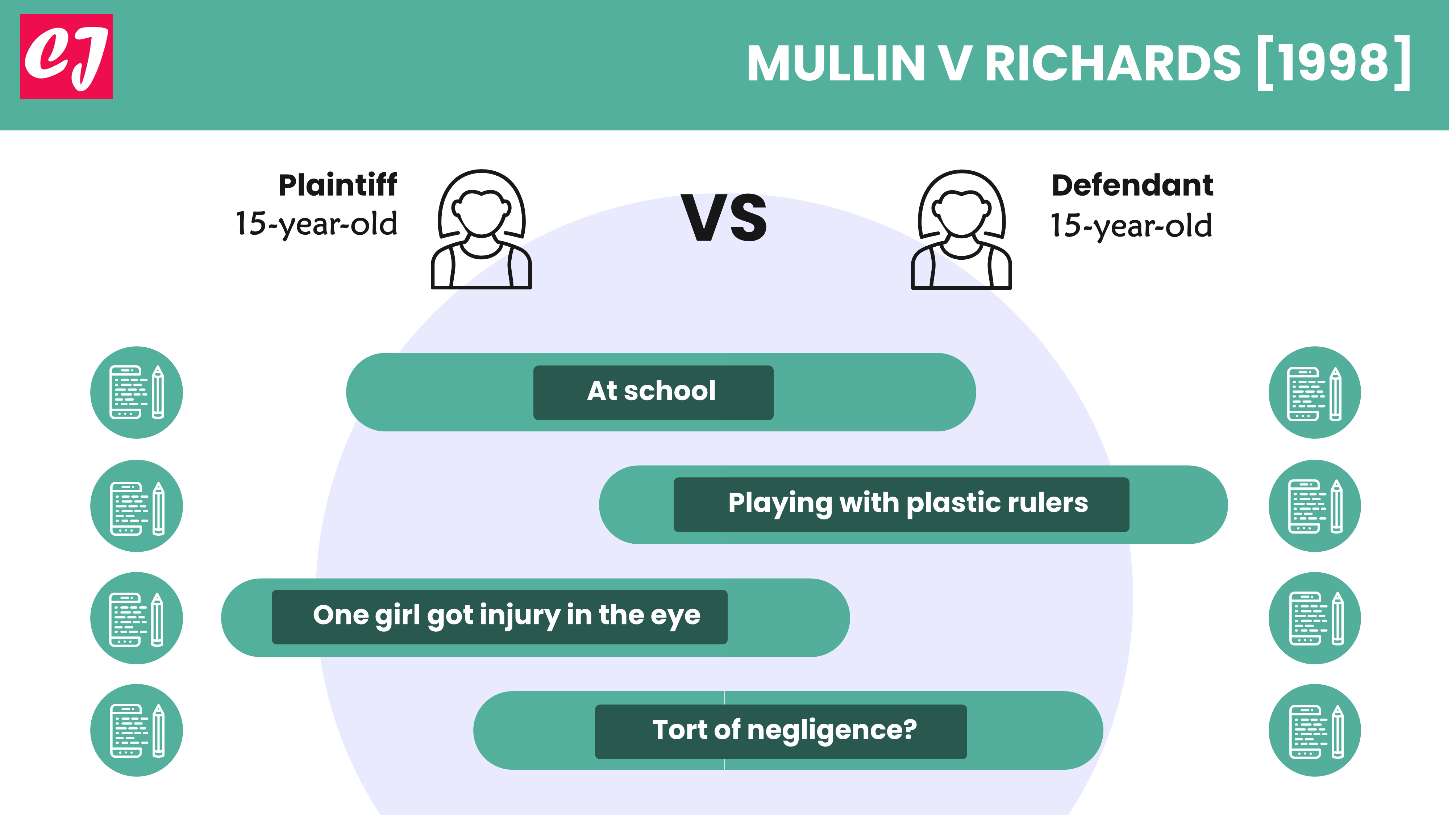

Case name & citation: Mullin v Richards [1998] 1 WLR 1304; [1998] 1 ALL ER 920 Case Overview This is a tort law case on…

Case name & citation: Revill v Newbery [1996] QB 567; [1996] 1 All ER 291; [1996] 2 WLR 239 What does the case deal with?…