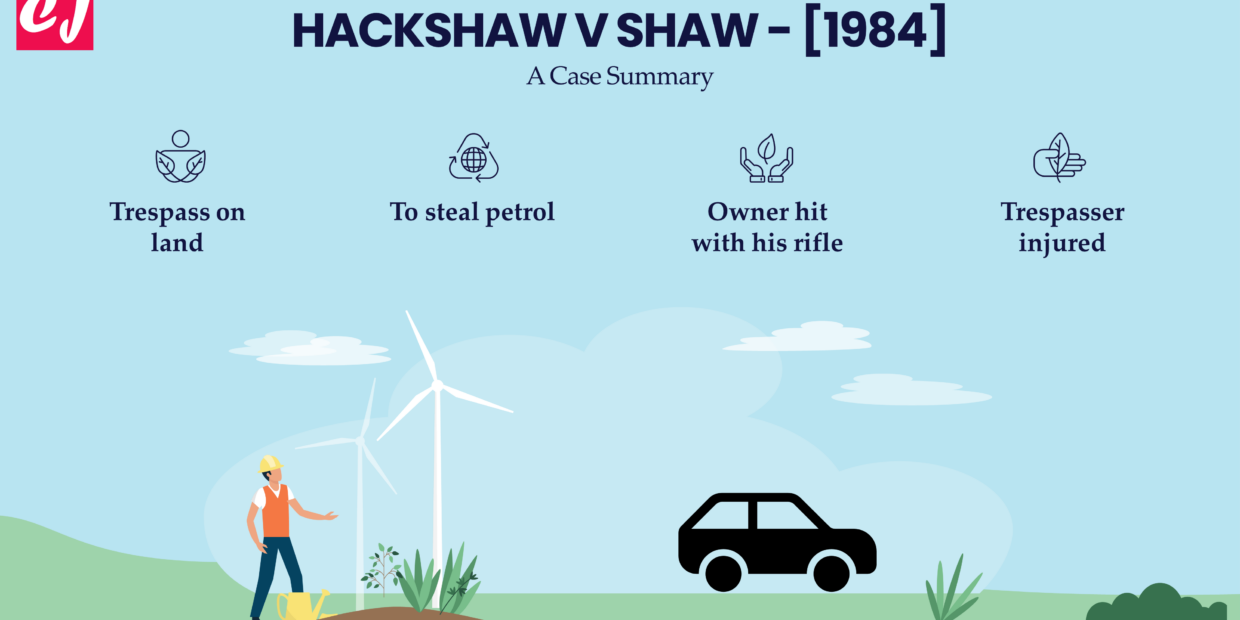

Case name & citation: Hackshaw v Shaw [1984] HCA 84; (1984) 155 CLR 614 What is the case about? Hackshaw v Shaw [1984] is a…

Rootes v Shelton (1967) is a tort law case that highlighted the extent to which participants in a sport or pastime may owe a duty…

Romeo v Conservation Commission of the Northern Territory (1998) is a widely recognized case from Australia. It concerns a negligence claim against the Conservation Commission…

Adeels Palace Pty Ltd v Moubarak [2009] is a tort law case involving a physical dispute at a restaurant whereby the plaintiffs got injured. Doubts…

Doubleday v Kelly [2005] is a tort law case concerning the foreseeability of risk and duty of care. Given below are the case details: Case…

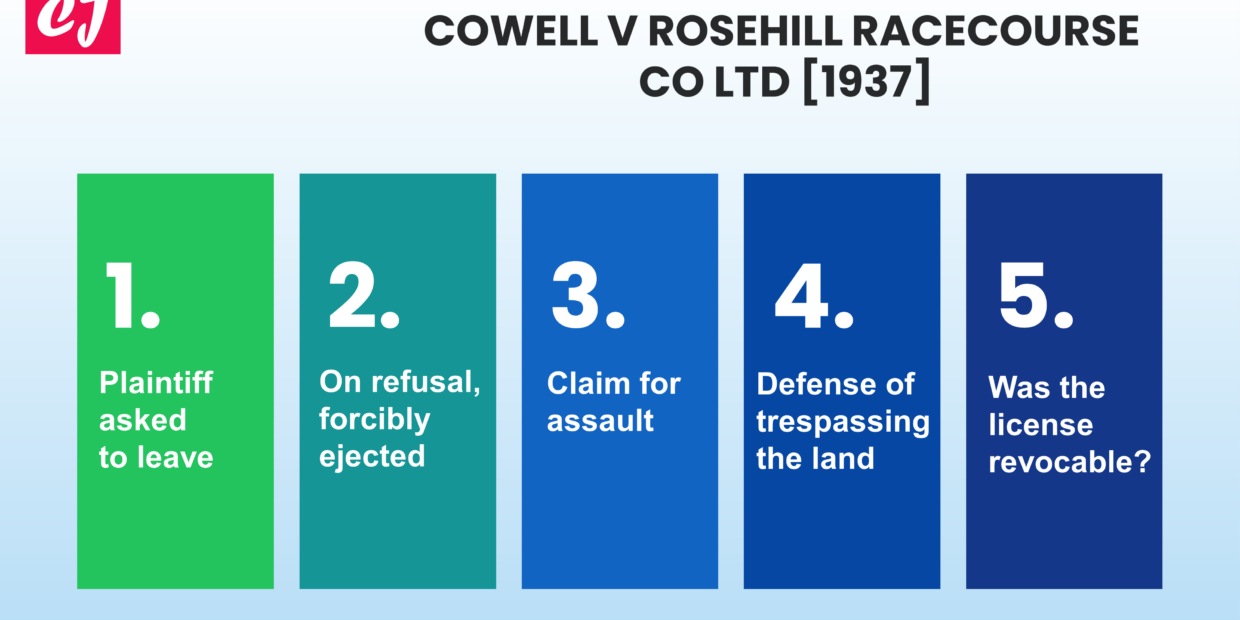

Cowell v Rosehill Racecourse Co Ltd [1937] is a tort law case from Australia differentiating between contractual rights and property rights. Case name & citation:…

Case name & citation: Zanker v Vartzokas (1988) 34 A Crim R 11 Zanker v Vartzokas (1988) is a legal case that involved a potentially…

The case of Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (1980) addressed the topic of negligence and whether a Council was irresponsible in placing a sign indicating…

Carrier v Bonham [2001] is a classic tort law case that deals with the liability of mentally ill individuals for negligence issues. The case discusses…

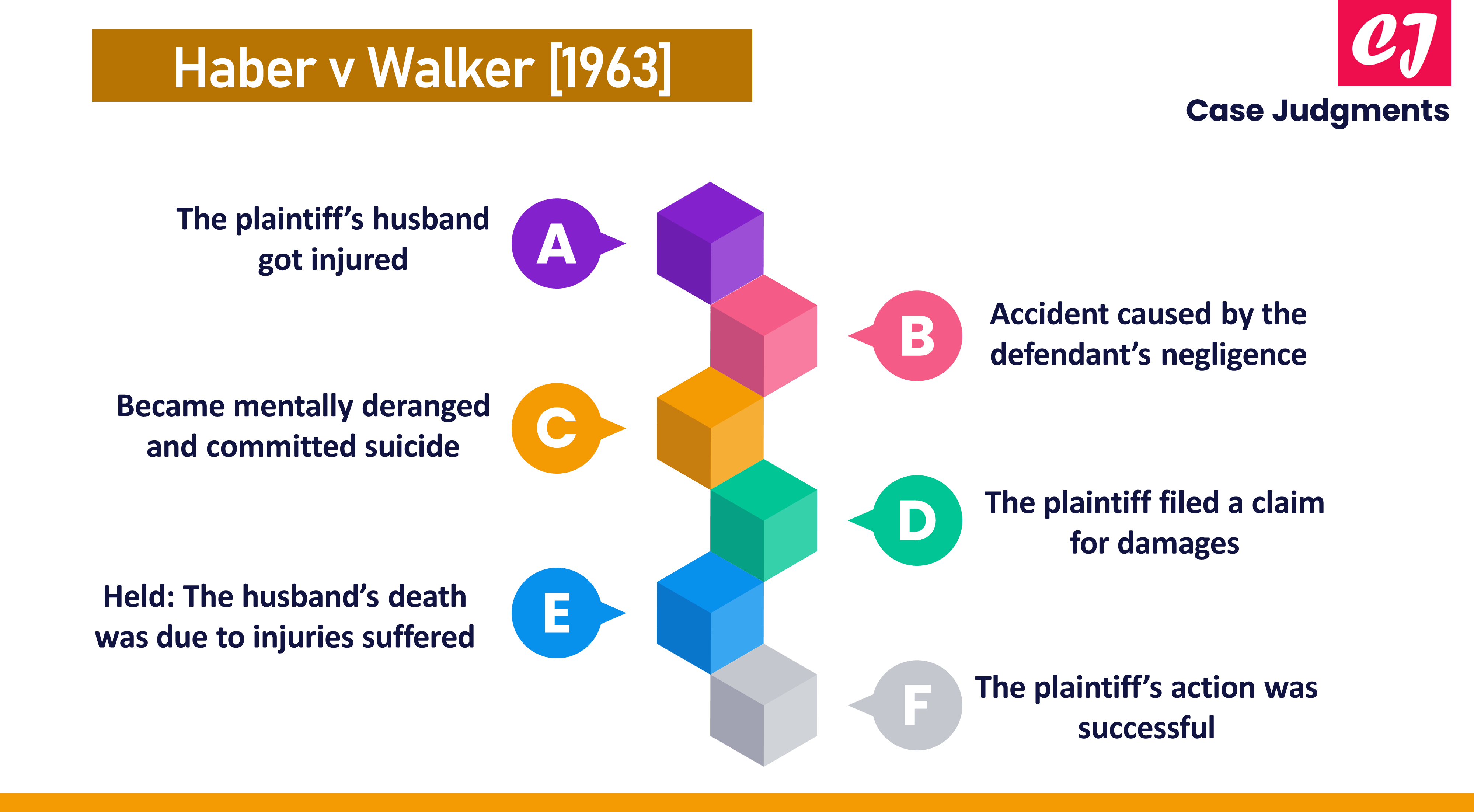

Haber v Walker [1963] is a tort law case on issues related to causation, foreseeability and novus actus interveniens. Here, as a result of the…