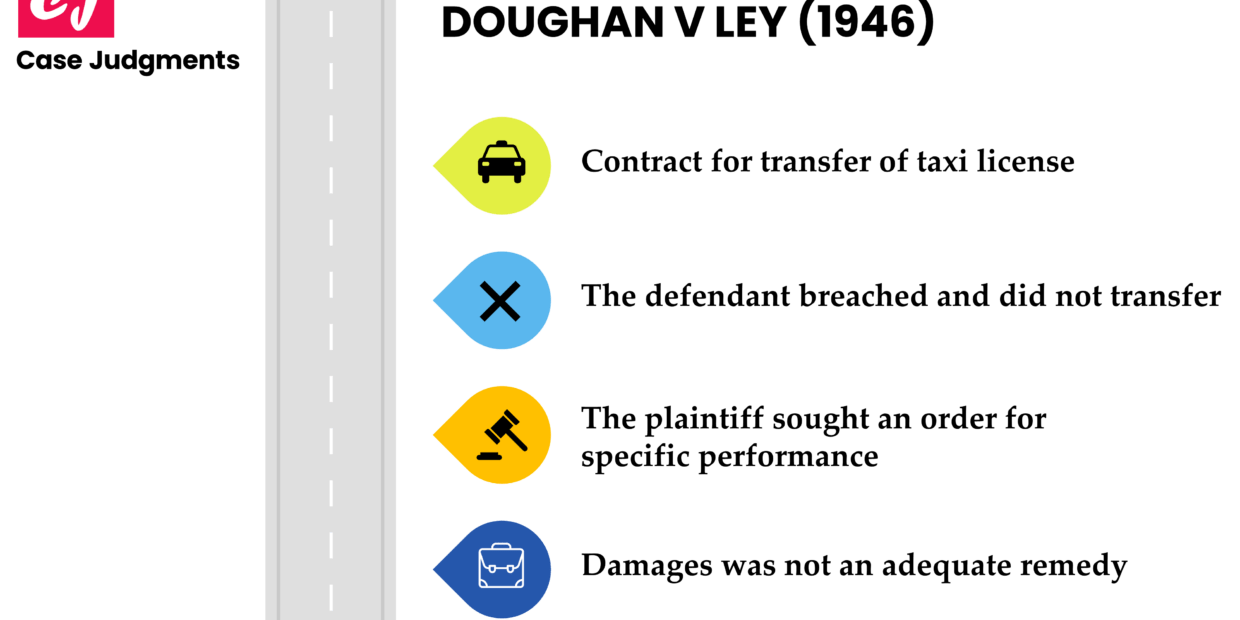

Dougan v Ley (1946) is an Australian case that throws light on the remedy of specific performance where there is a breach of contract. It…

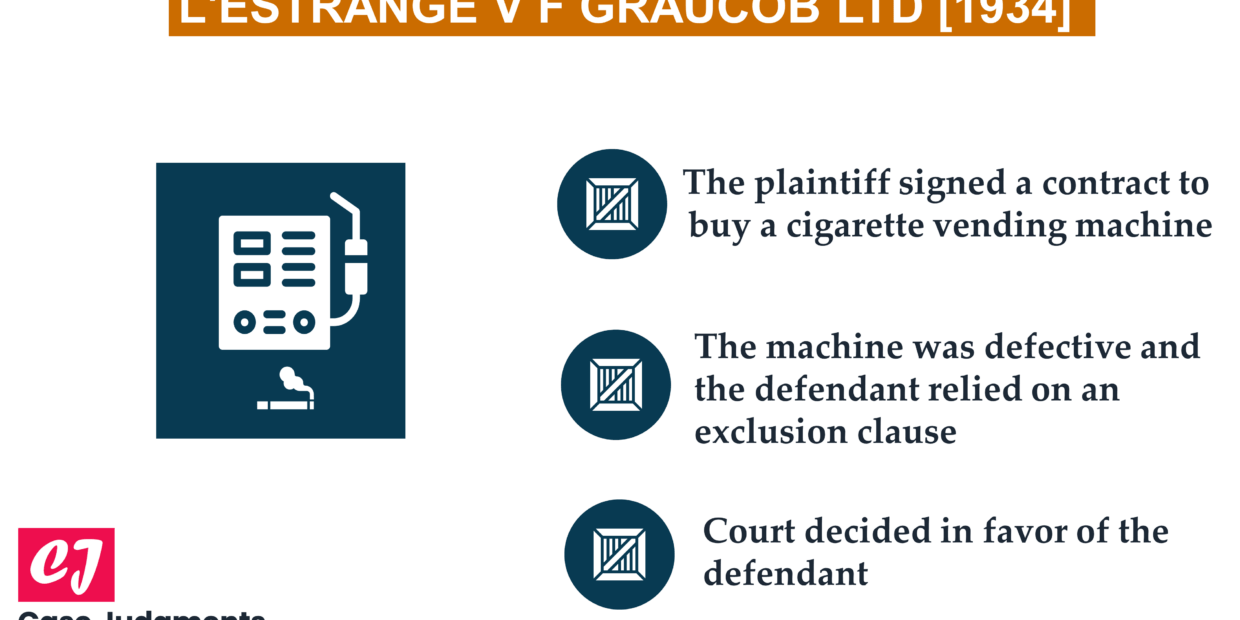

L’Estrange v Graucob [1934] is a famous contract law case that is known for laying down the rule that the contents of a signed contract…

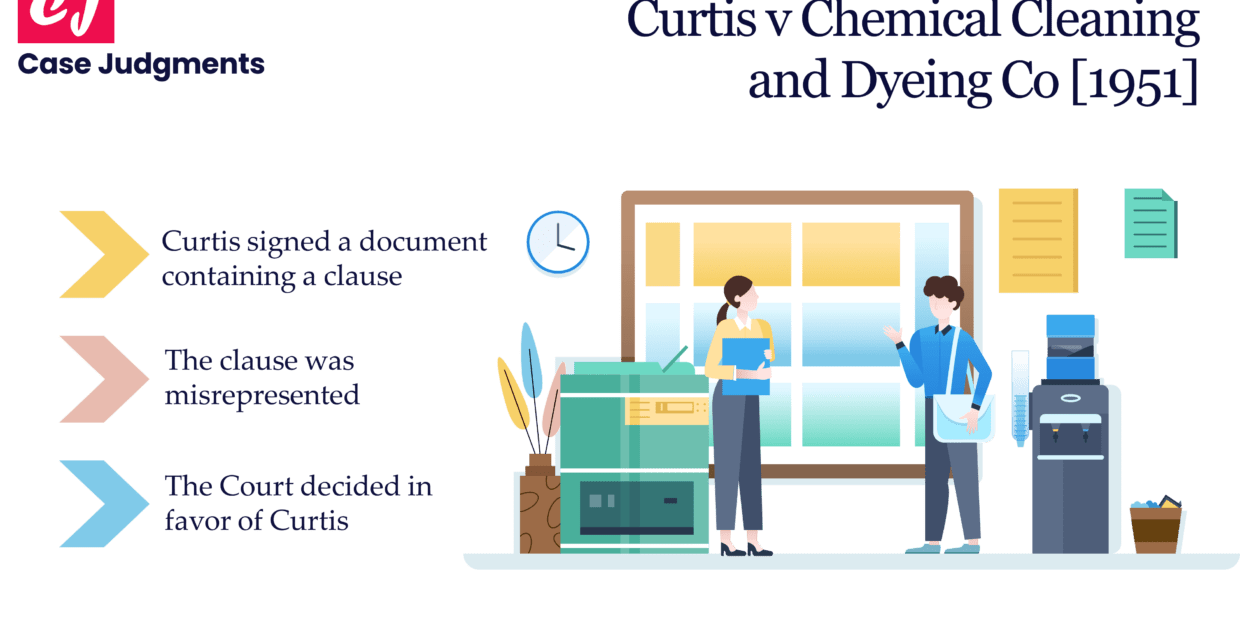

Curtis v Chemical Cleaning and Dyeing Co [1951] is a famous contract law case that dealt with the issue of misrepresenting a term. It determined…

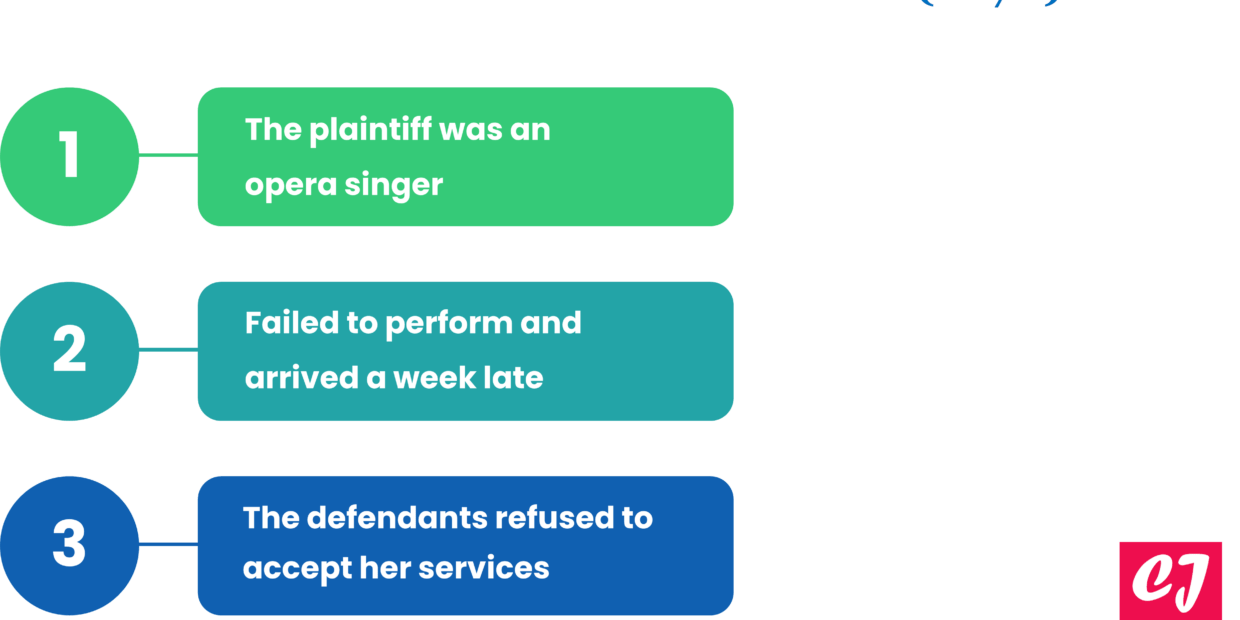

Case name & citation: Poussard v Spiers and Pond (1876) 1 QBD 410 What is the case about? This is a famous contract law case…

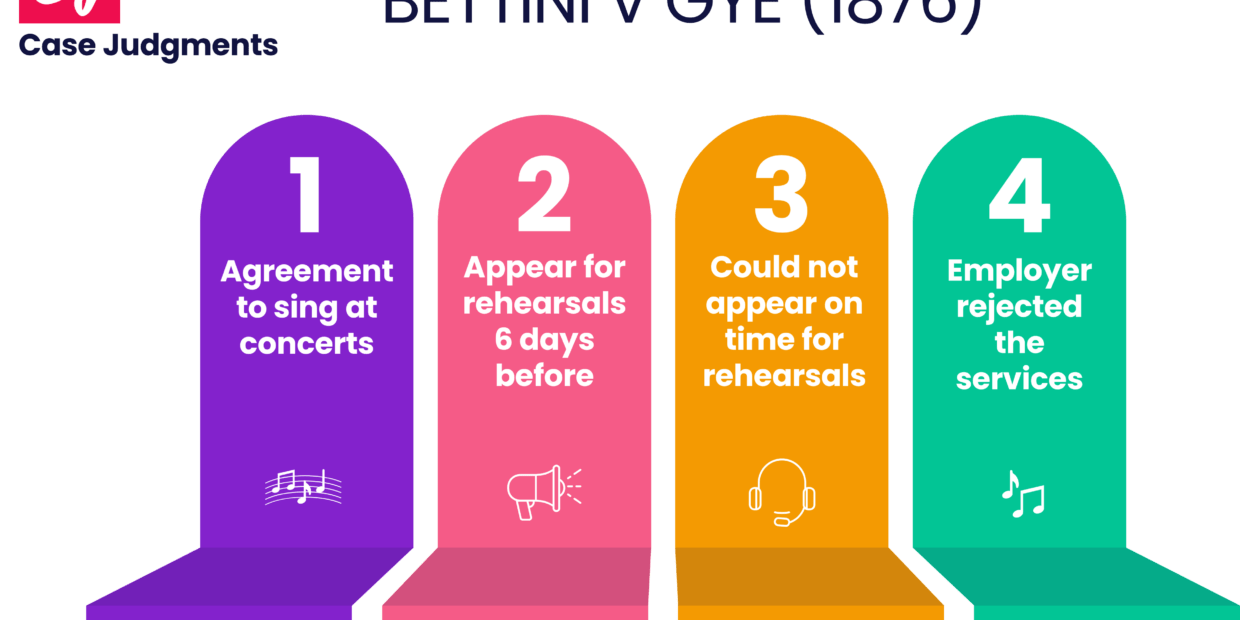

Case name & citation: Bettini v Gye (1876) 1 QBD 183 What is the case about? In the landmark case of Bettini v Gye (1876),…

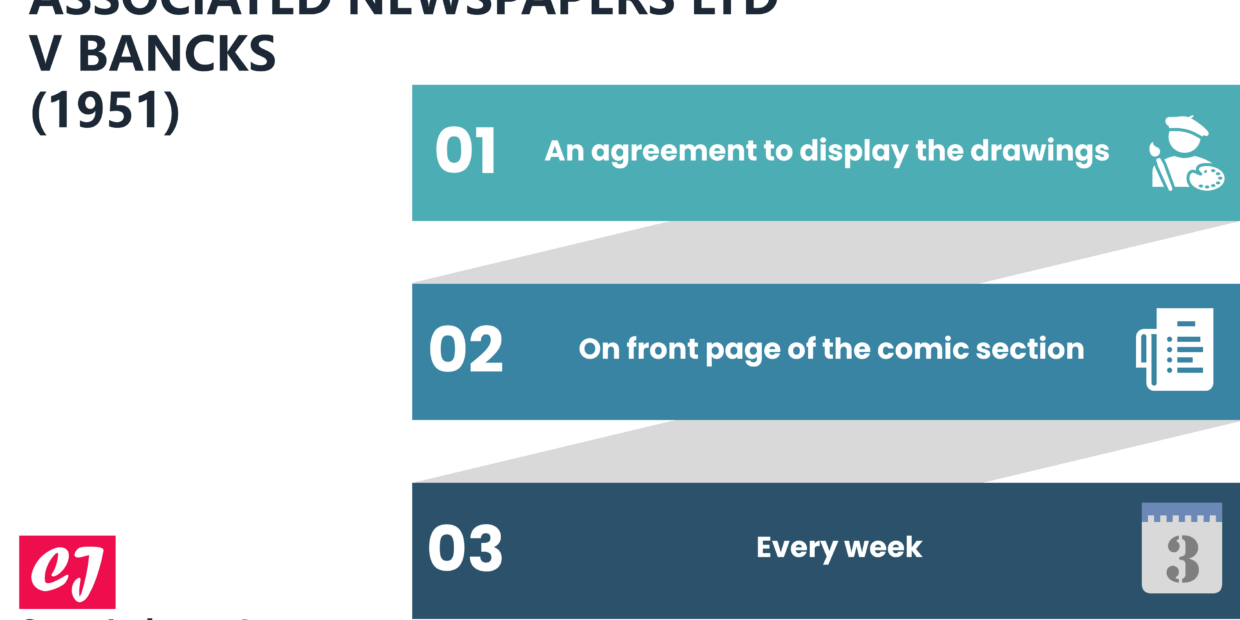

Associated Newspapers Ltd v Bancks is a UK contract law case that deals with the test of essentiality. The test is to determine whether a…

The courts use a test of “essentiality” to decide whether a term is to be interpreted as a “condition.” This test was famously explained by…

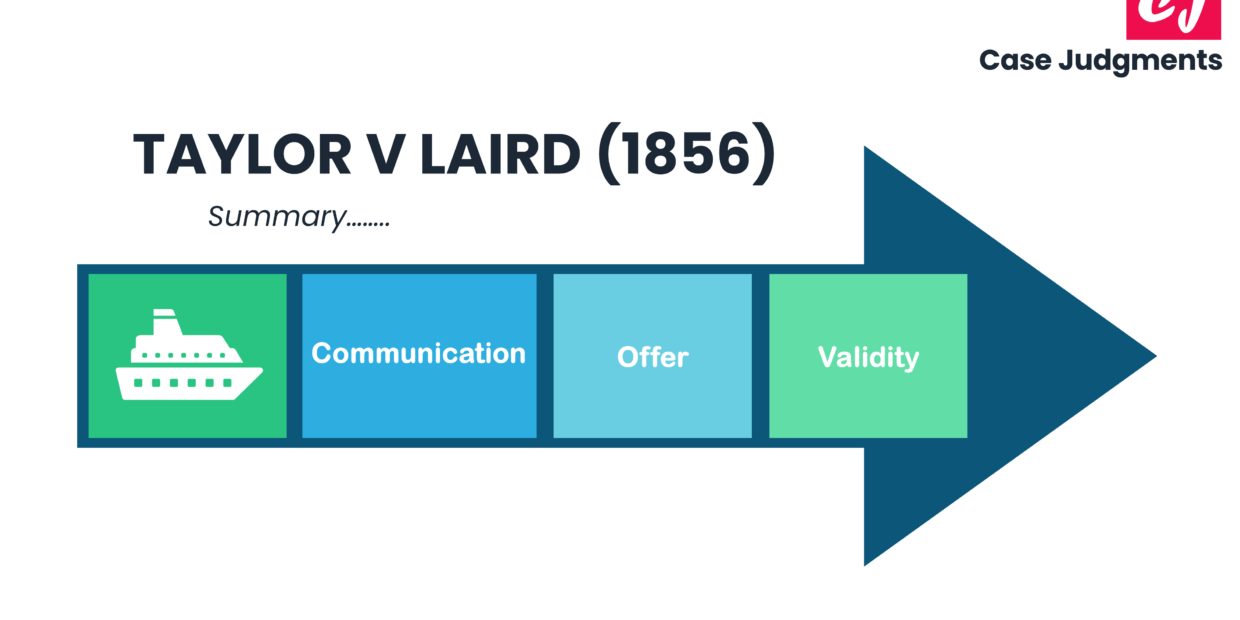

Case name & citation: Taylor v Laird (1856) 25 LJ Ex 329; (1856) 1 H & N 266 What is the case about? Taylor v…

Case name & citation: Atlas Express Ltd v Kafco (Importers and Distributors) Ltd [1989] 1 All ER 641; [1989] QB 833; [1989] 3 WLR 389…

Case name & citation: Spencer v Harding (1870) LR 5 CP 561 What is the case about? Spencer v Harding is a legal case in…